Re-evaluating First Contact in Light of New Technology

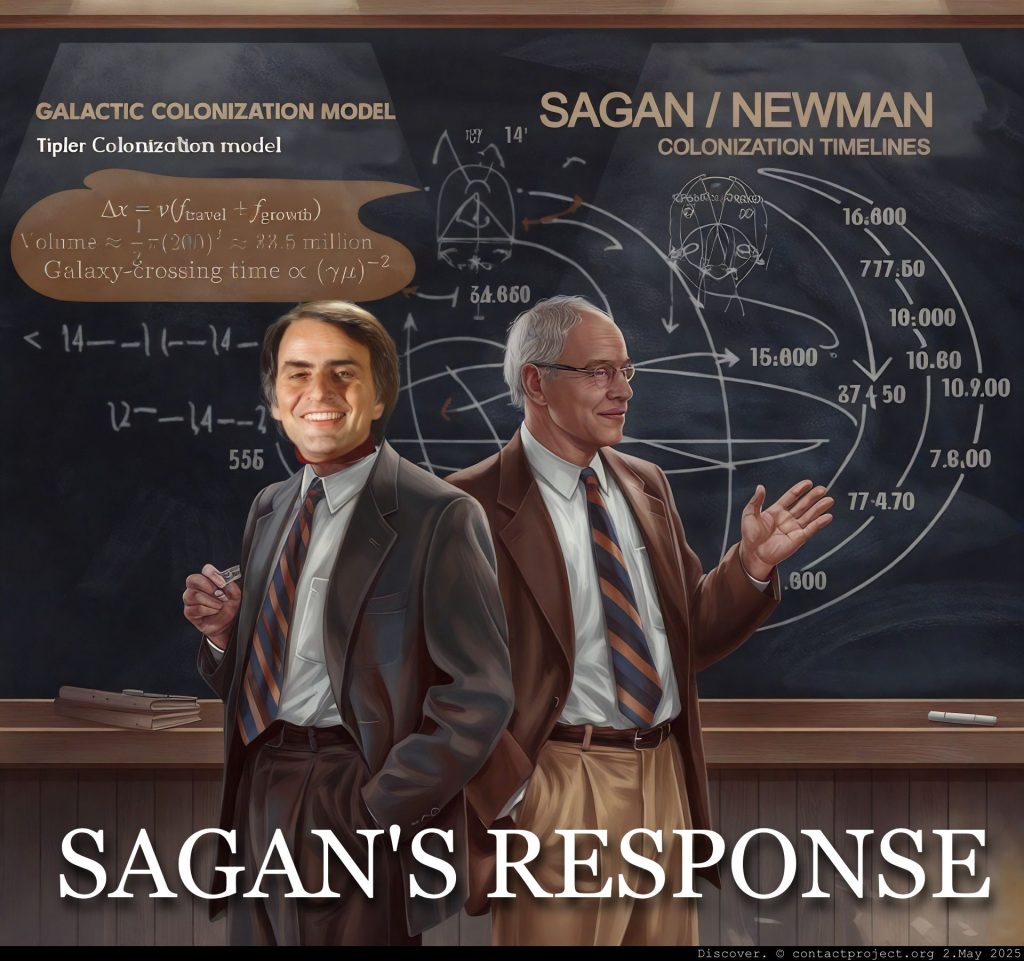

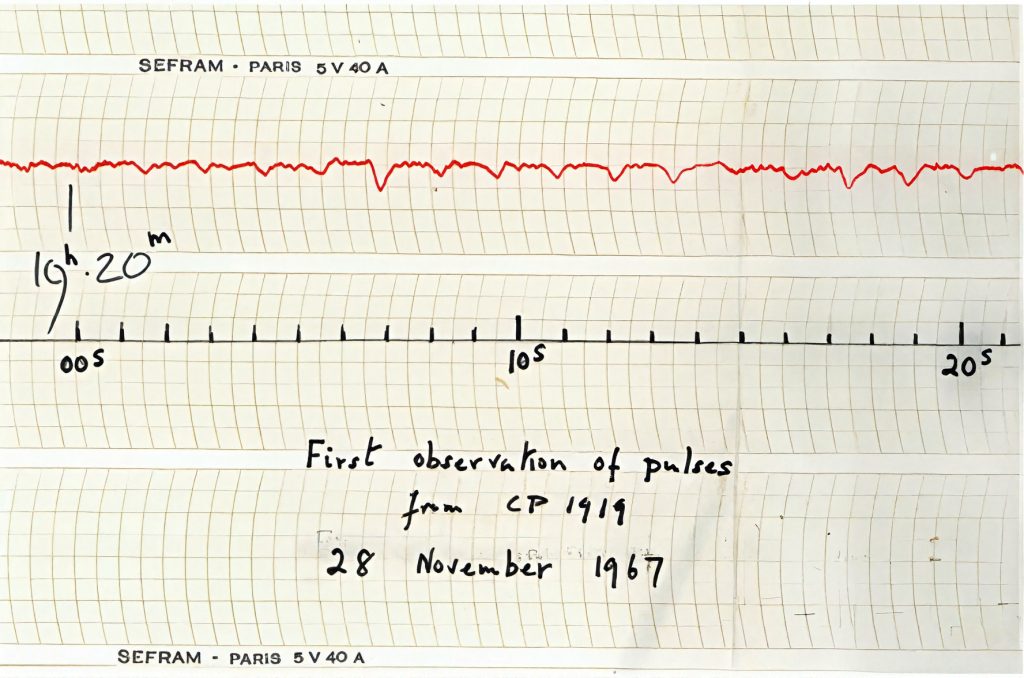

The Old Challenge: Sagan’s Paradox

Carl Sagan calculated in 1969 that to initiate the first contact between humans and aliens, we would need to launch 10,000 spaceships into space annually to have even the remotest chance of success. This endeavor would collectively consume about 1% of the mass of all stars in the universe for building materials. Therefore, it makes the task seem impossible.

The Modern Solution: Breakthrough Initiatives

Today, billionaires Yuri Milner and Mark Zuckerberg challenge this paradox. Their “Breakthrough Initiatives” is a scientific effort to find extraterrestrial intelligences. They aim to contact them and explore nearby planets.

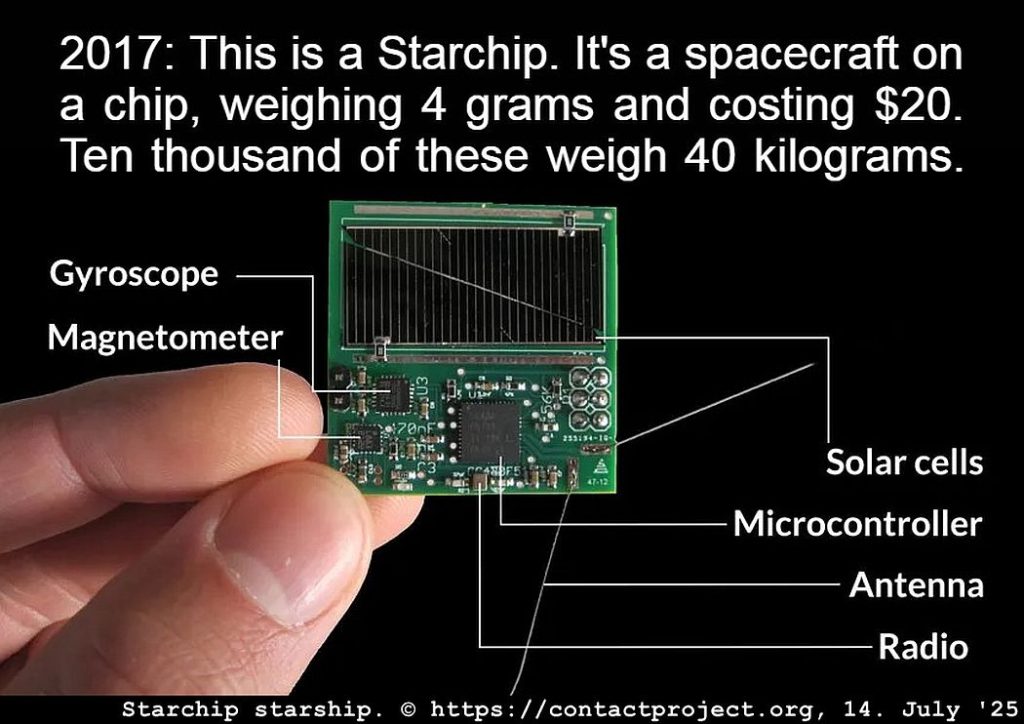

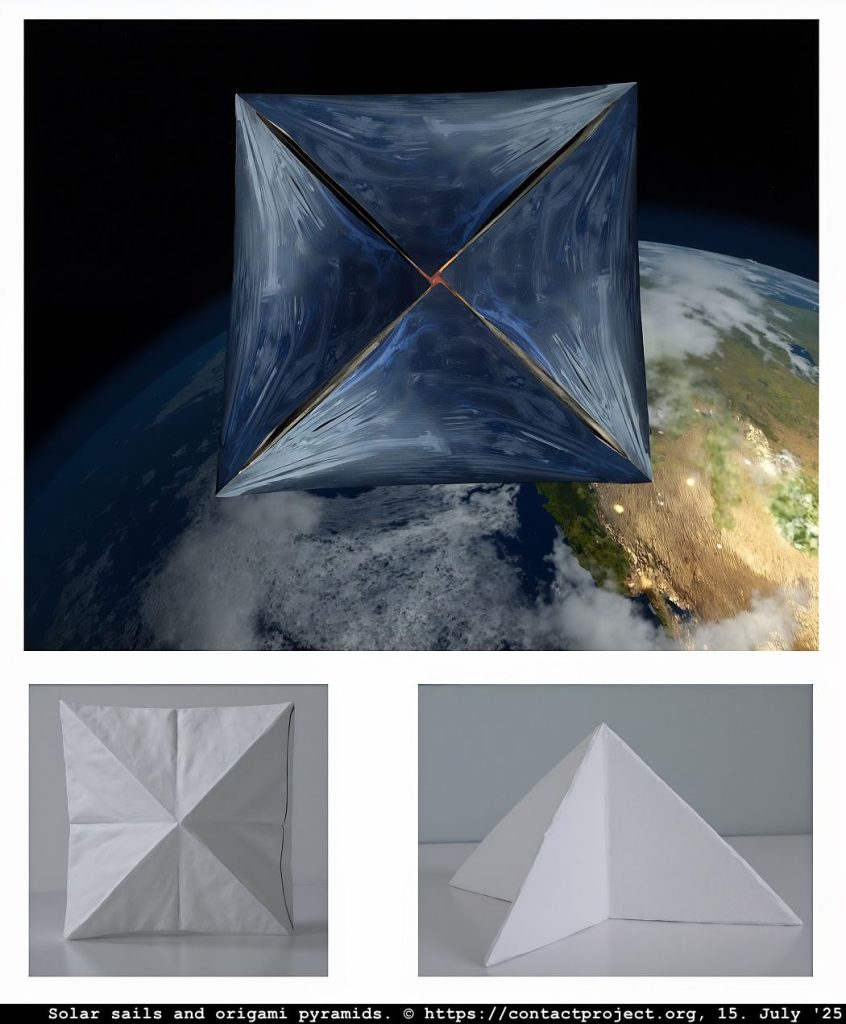

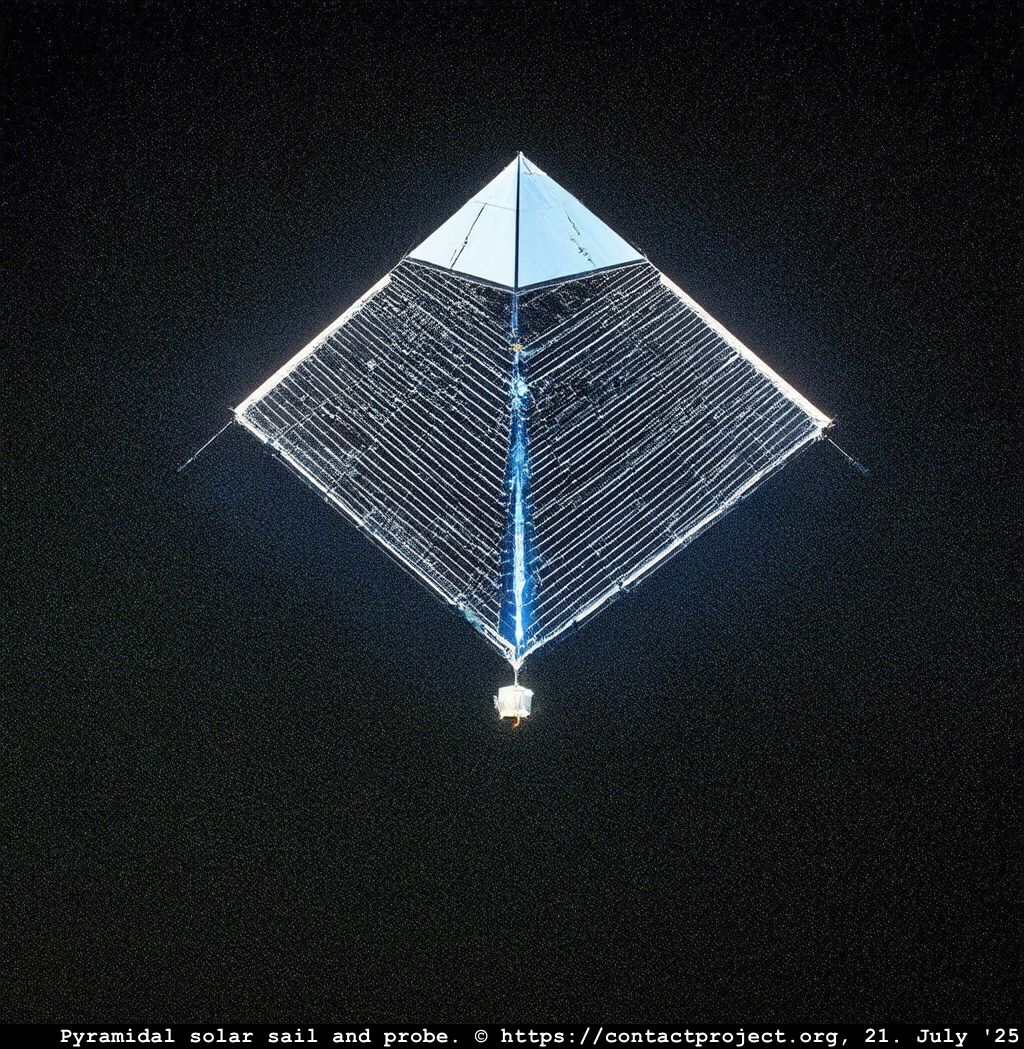

Programs like “Breakthrough Starshot” want to send inexpensive unmanned probes, called “StarChips,” to nearby solar systems. They plan to first target Proxima B. The “StarChip” is a marvel of miniaturization. It contains a camera, battery, radio module, solar cells, a photon drive (an LED), and various instruments. Remarkably, it weighs only a few grams.

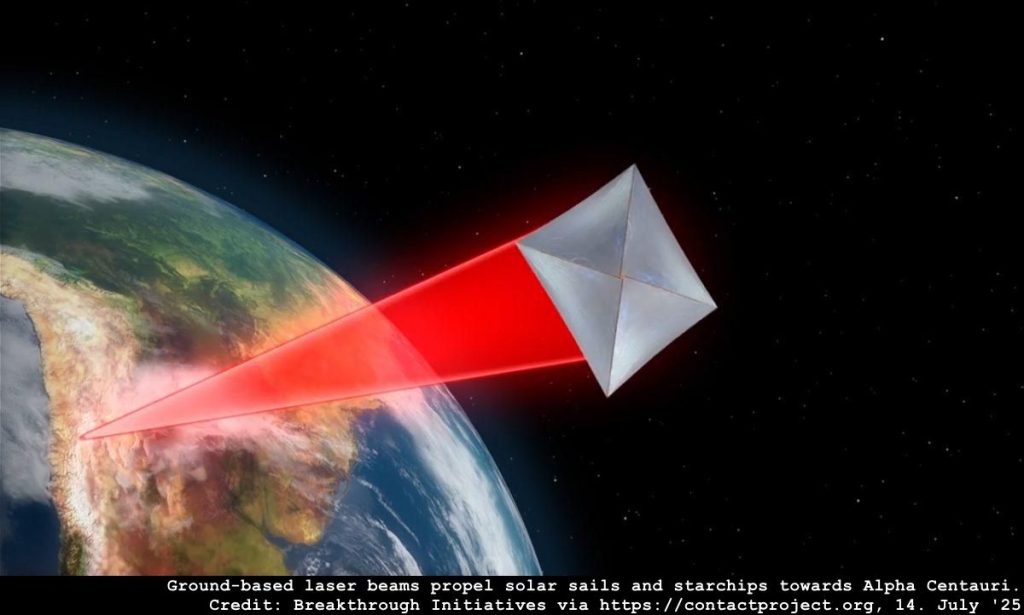

These nanoprobes will attach to solar sails. This enables laser-assisted accelerations of up to 15-20% of the speed of light. At those speeds, we can reach Alpha Centauri in 20-30 years. Unlike past concepts like the Longshot project, which would require billions of dollars for a single probe, a StarChip nanoprobe costs only around $20.

The launch laser constitutes the biggest cost factor. The project estimates a one-time investment of 5-10 billion dollars for the entire system. Once built, this laser could launch millions of probes. Harvard astronomer Avi Loeb suggests we could send these probes to every corner of the cosmos every year, without breaking a sweat.

So, we now see that the material required to send 10,000 probes to the stars every year is only about 40 kilograms. It doesn’t require a significant proportion of the mass of the universe. That’s good.

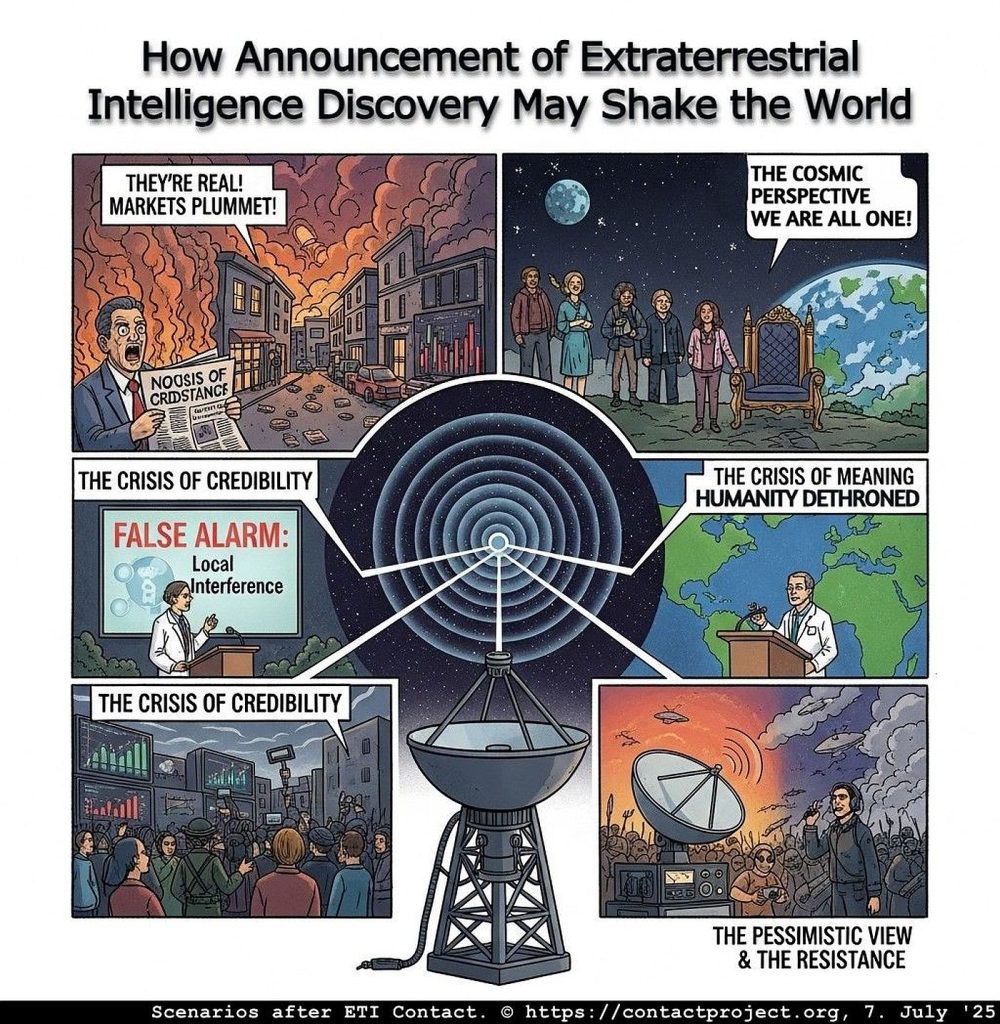

This technological leap invites a profound question. What influence could the sighting or salvage of a StarChip-like probe have on extraterrestrial intelligent beings on their planets?

Cosmic Mirror

Think of the search for aliens as holding up a giant mirror to all of humanity. By looking for others out there, we end up looking for ourselves. It forces us to think about the signals and objects we’re sending into space and what it means to a planet full of people.

Erich Habich-Traut

The “Cargo Cult” Hypothesis

Could an alien “Starchip”-like probe have landed on Earth in the past?

Sagan himself did not rule out that Earth had been visited by aliens, a priori. Yet, he was a strong opponent of Erich von Däniken’s idea that aliens were directly involved in building the pyramids. Nevertheless, the origin myths of humankind, particularly from Mesopotamia and Egypt, pose intriguing questions.

Mythological Parallels: Echoes of a Visitation?

The cultures of Mesopotamia and Egypt play a major role in the origin myths of humankind.

According to the Egyptian creation myth of Heliopolis, in the beginning, there was endless, deep, dark water. From this roiling abyss a solitary, pyramidal mound called the Benben stone arose; the first point of order. Here a solitary intelligence, the sun god Atum-Ra, came into being. Alone, he brought forth two sentient forces: his son and daughter. He sent them out, to begin the great work of building a universe.

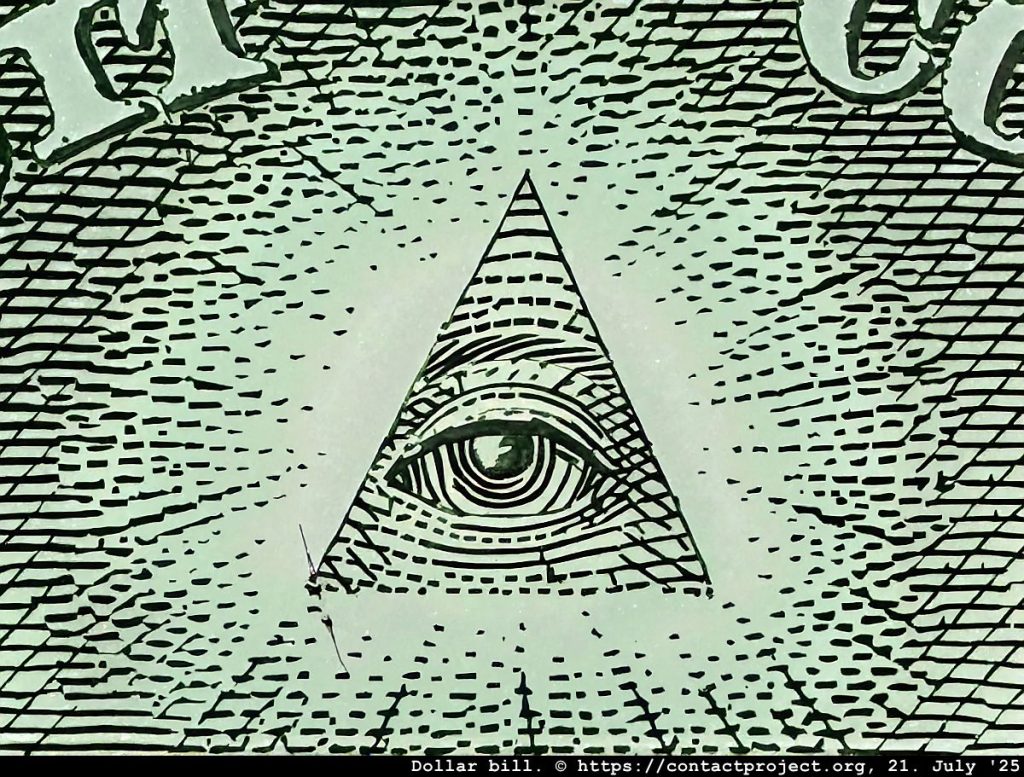

For a time, his children were lost. In his desperation, Atum-Ra decoupled a fragment of his consciousness, a sentient probe he called an Eye. He then sent it out to find his children. The eye roamed the vastness, found and returned the children to the pyramidal mound. Atum-Ra’s tears of joy fell on the Earth, and humanity was created.

Thereafter, Atum-Ra began sailing across the heavens in the solar boat of a million years.

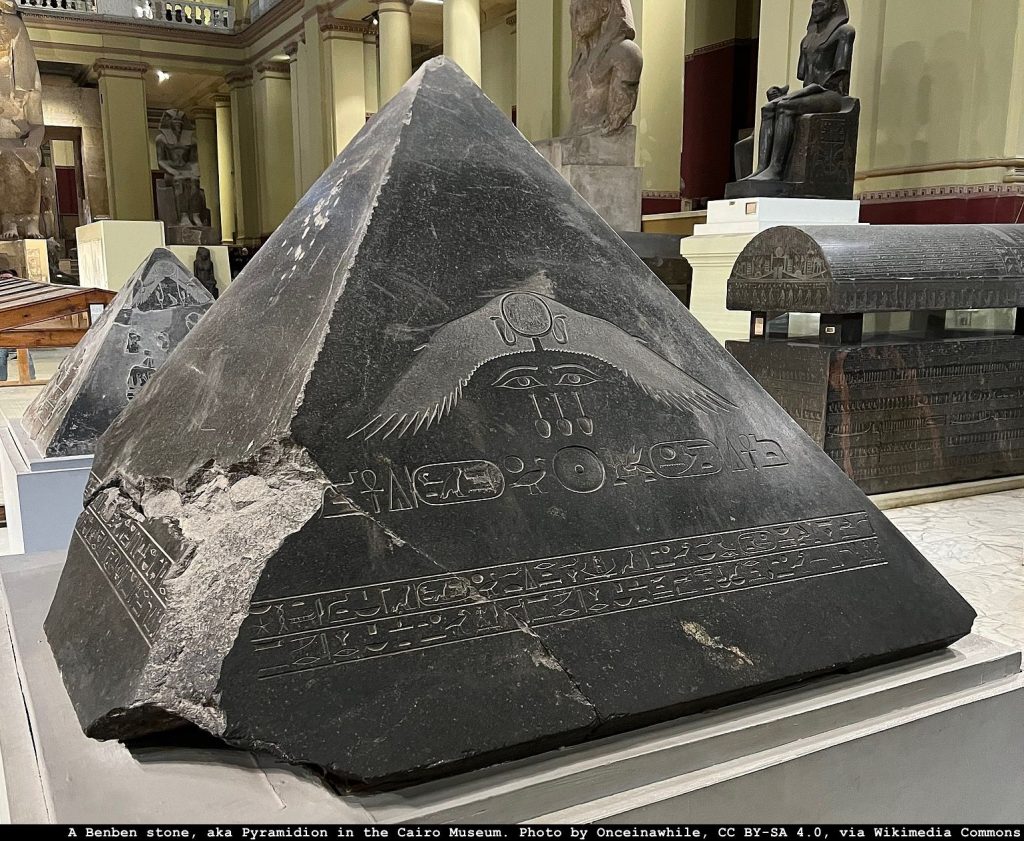

Benben stones…

…had great spiritual importance, they were the capstones of pyramids or obelisks. They represented the primordial mound from which the world was created.

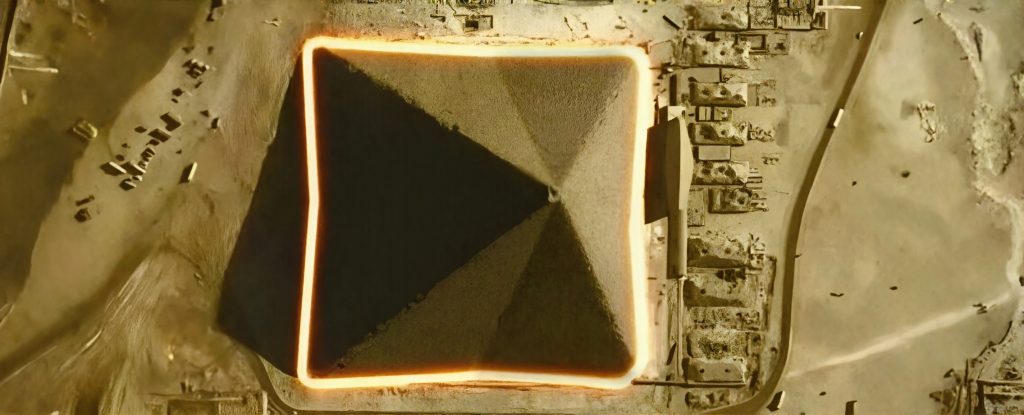

Intriguingly, some solar sails, for instance those from the Breakthrough Starshot program, can bear a striking resemblance to a pyramid shape:

From the Egyptian creation story to the Sumerian Gilgamesh epic and the Bible, scout birds or flying eyes are common motifs. These epics also feature great bodies of water and voyages to find land.

In these tales it has always been the task of scout birds and divine messengers to find or return to a home for humankind. According to myth and legend, humanity arose on Earth from pyramidal “ships” or mounds – whether through offspring or tears.

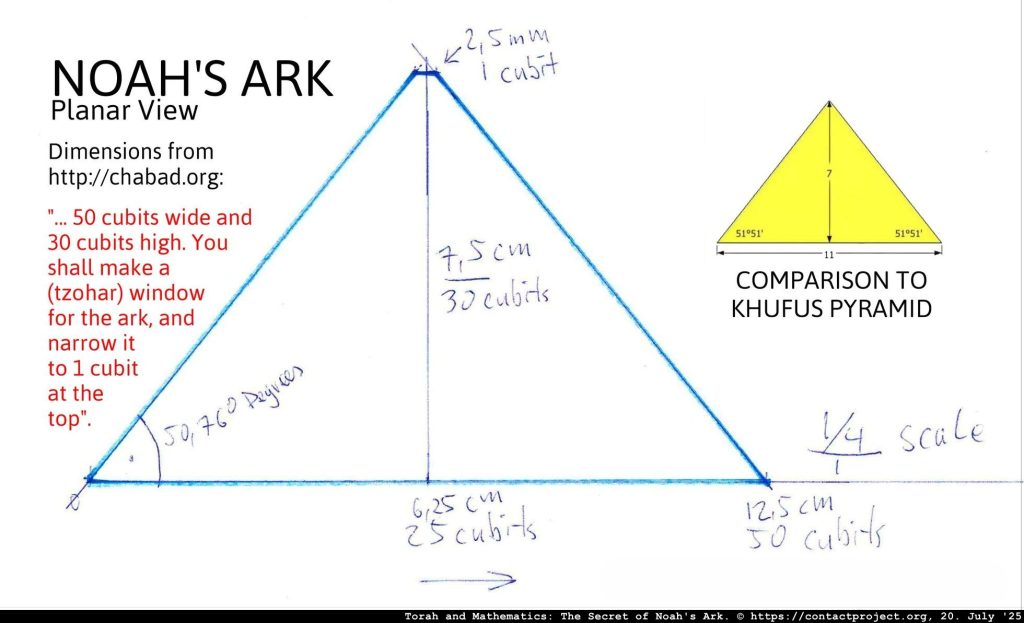

Noah’s Ark as a pyramid?

There are a number of examples in art that depict the Ark as a pyramid.

And it is not only some Renaissance sculptors and painters that depict Noah’s Ark as pyramidal. How did they come to this notion anyways? Haven’t we been taught in Sunday school that the Ark was a rectangular type boat shape? Maybe with a sloping roof?

Well, the idea of a pyramid -shaped Ark had been suggested much earlier, for instance by Origen of Alexandria in the 3rd century:

“I think that the ark, as much as is clear from the things that are described, had four angles rising from the bottom that gradually narrowed as they came to the peak and came together in the space of one cubit. Thus the cubit is the length and width of the peak.”

Torah Scholarship

This is echoed by the rational-mysticism school within the Chabad-Lubavitch movement of Orthodox Judaism. They explain that the Torah’s measurements prescribe a pyramid-shaped ark. I followed their instructions and drew this image:

Scientific Evidence

These interpretations are backed up by a recent analysis of the Dead Sea Scrolls. It suggests that Noah’s Ark was described as having a pointed, pyramid-like roof.

This discovery was made possible by a project at the Israel Antiquities Authority. It used high-resolution scanning technology to reveal previously illegible text on the ancient parchments.

A Monument to a Memory

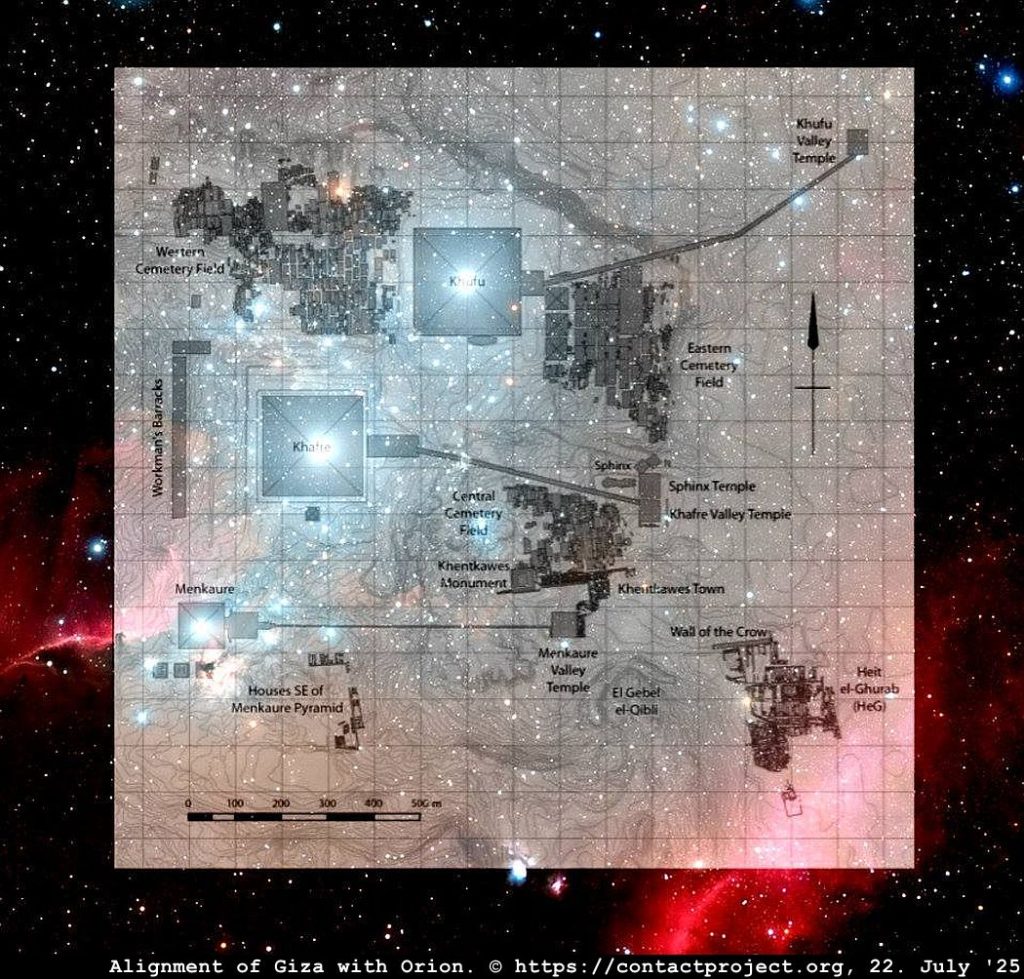

The convergence of evidence from archaeology, mythology, religious texts, and astronomy does not suggest that aliens built the pyramids.

Rather, it points toward a more compelling and profoundly human explanation. The pyramids are the ultimate expression of a prehistoric cargo cult. The argument is not that extraterrestrials directed their construction. Instead, our ancestors witnessed a singular, awe-inspiring event: the arrival of an autonomous or crewed probe from another world, perhaps resembling a modern solar sail, i.e. pyramidally shaped.

In any case, this “visitor,” with its pyramidal shape, would have been interpreted through a religious lens. It wasn’t a technological marvel; it appeared as a divine messenger. The recurring motifs across cultures – the pyramidal Benben stone from which life arose, the pointed roof of Noah’s Ark that saved humanity from the water, and the “Eye” of Ra sent to search the world – can be understood as fragmented cultural memories of this single technological apparition.

Faced with an event far beyond their comprehension, ancient peoples did what humans have always done: they sought to understand it, venerate it, and reconnect with it. They built pyramids not under alien instruction, but as a monumental act of imitation and worship.

These structures were humanity’s attempt to recreate the form of the “divine” object. They hoped to summon its return. Therefore, the pyramids are not an alien artifact, but an enduring monument to human awe and our innate drive to make sense of the unknown.

Sons of Orion

“The Nephilim were on the earth in those days – and also afterward – when the sons of God went to the daughters of humans and had children by them. They were the heroes of old, men of renown.”

Genesis 6:4

In the Aramaic language, a Semitic tongue closely related to Hebrew, the constellation Orion is known as Nephila (נְפִילָא). This has led some scholars to propose that the Hebrew “Nephilim” might be linked to this Aramaic term.