A friendly, fact-based rebuttal to Zechariah Sitchin’s Anunnaki story

1. Setting the Stage

In 1976, self-taught scholar Zechariah Sitchin published The 12th Planet, launching the idea that a race of extraterrestrials called the Anunnaki genetically engineered early humans to dig up Earth’s gold. The motive, he claimed, was to save the Anunnaki’s distant home world by dispersing that gold into their planet’s atmosphere.

Forty-plus years later the theory still floats around TikTok, YouTube, and late-night radio—but it stumbles over one gigantic 21st-century fact: asteroid mining is a far simpler, safer, and richer way to collect precious metals than forcing a brand-new species to do back-breaking labor on a heavy-gravity world.

Let’s walk through the real science and economics:

2. Gold in Space: A Galactic Free-for-All

- A single metallic asteroid just 1 kilometer across can hold more platinum-group metals than have ever been mined on Earth. (Mining the sky)

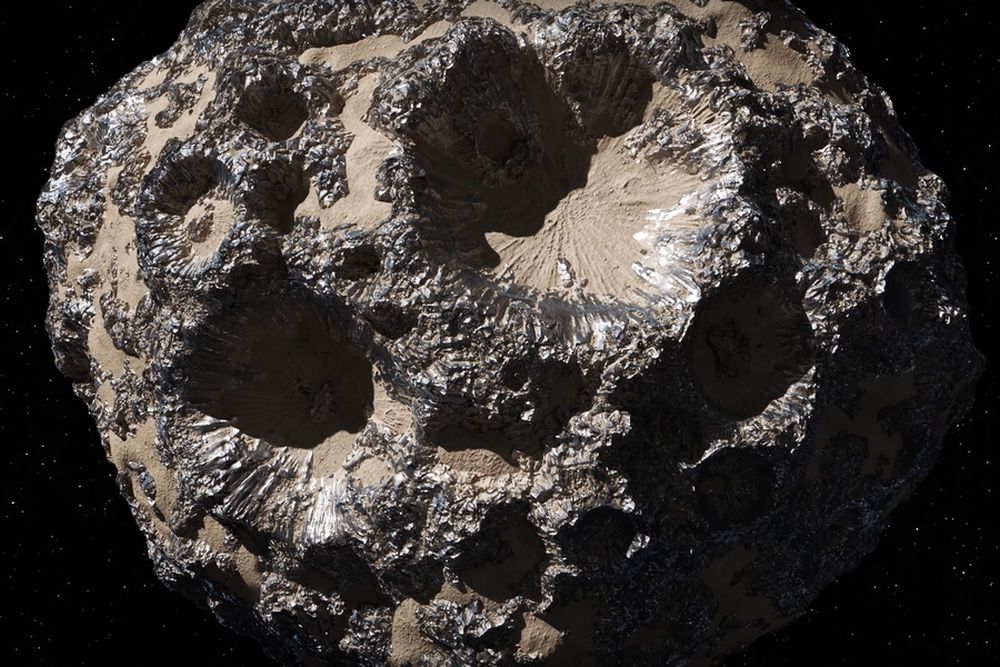

- NASA’s Psyche mission, launched 13 October 2023, is headed toward 16 Psyche—an asteroid thought to be 60 percent iron and nickel, with traces of gold and platinum worth an estimated \$10,000 quadrillion (that’s a 1 followed by 19 zeros).

- The asteroid belt, located between Mars and Jupiter, contains millions of these metallic bodies, all drifting in vacuum with essentially zero atmospheric drag.

In short, space is swimming in easy-to-reach metals. Why would any advanced species bother landing on a planet, fighting 9.8 m/s² of gravity, and supervising rebellious primates?

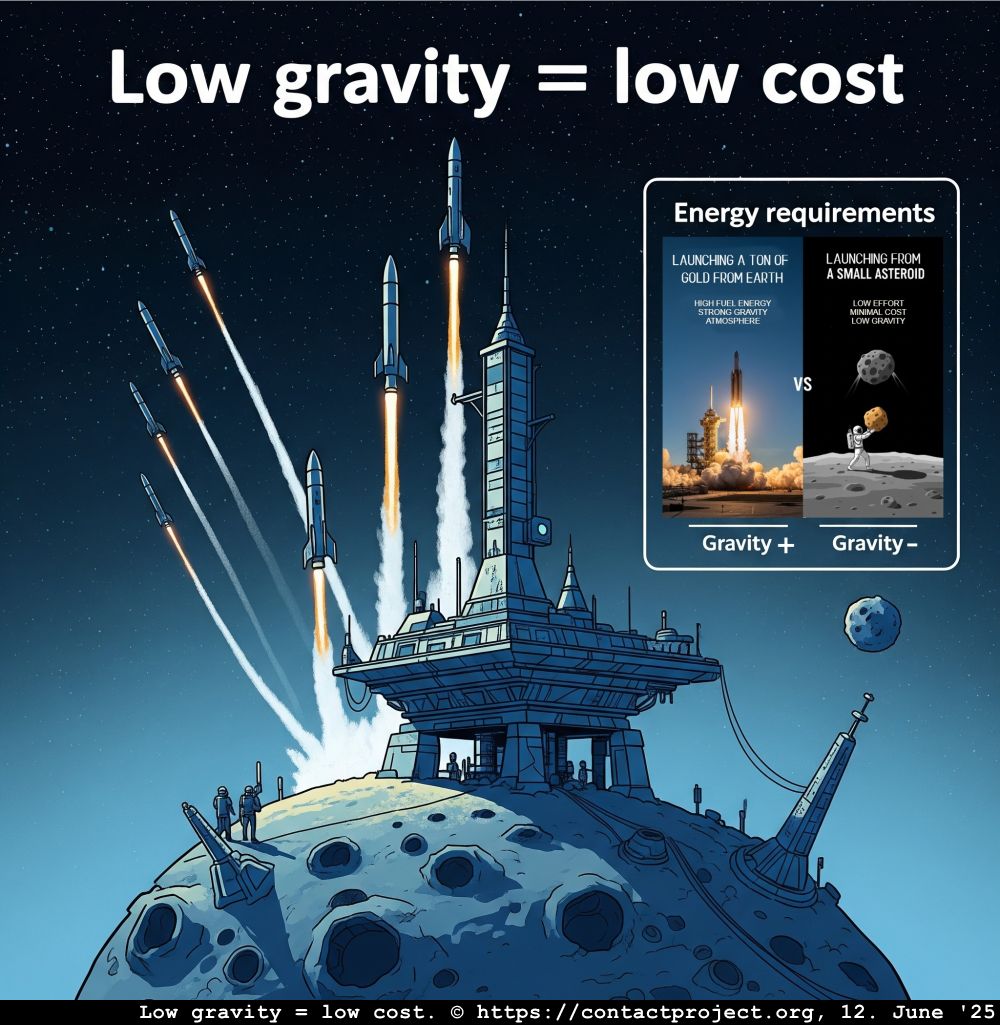

3. Physics 101: Hauling Ore Where Gravity Is Tiny

Earth’s escape velocity—how fast you must go to break free of our planet—is 11.2 km/s. From a typical near-Earth asteroid it’s often < 1 m/s.

If you want to launch one ton of gold off Earth, you need a gigantic rocket and a lot of fuel. If you want to launch that same ton from a small asteroid, you can throw it with the force of a good fastball.

Low gravity equals low cost. Any civilization capable of interstellar travel would recognize that.

4. Tech We Already Have (and Tech We’re Building)

- Prospecting:

• Tiny “CubeSats” like NEA Scout carry telescopes and spectrometers to identify metal-rich candidates.

• Commercial start-ups—Astroforge and Asteroid Mining Corporation—have filed dozens of patents on micro-probes that can swarm an asteroid and map its composition. - Excavation:

• The European Space Agency’s Hera mission will test robotic drills and anchoring harpoons in 2026.

• Autonomous “mole” robots can tunnel without human presence, solving the classic “who holds the shovel?” problem. - Processing and Transport:

• A solar furnace can melt ore directly in vacuum—no atmosphere means no heat loss.

• Electromagnetic rail guns or rotating tethers could fling sealed metal ingots to pre-set orbits, no rockets required.

If humans in 2024 are prototyping these systems, imagine what a million-year-old species could do.

5. The Economics: It’s a No-Brainer

- Cost to lift 1 kg from Earth to low orbit: ≈ \$3,000 with today’s SpaceX Falcon 9 rates (and that’s the cheapest option).

- Cost to lift 1 kg from a small asteroid to low-Earth orbit: estimated at \$30–\$50—almost two orders of magnitude cheaper once the infrastructure is deployed.

Yes, asteroid mining demands an upfront investment, but an advanced civilization likely thinks on geological time scales. Training, feeding, and controlling a population of brand-new hominids for thousands of years? That’s a management nightmare—and a wildly risky business model.

6. What About the Ancient Texts?

Sitchin claimed that Sumerian cuneiform tablets describe the Anunnaki’s gold quest. Modern Assyriologists disagree:

- The tablets can be read in standard Akkadian and Sumerian; they mention no alien planets, no genetic labs, and no gold shortage.

- Sitchin’s translations often swap syllables or invent words that don’t exist in Mesopotamian lexicons.

In archaeology, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. No skeletons of alien “foremen,” no laser-cut mines, no hybrid-human DNA patterns have ever turned up.

7. The Science-Fiction Counterpoint

The idea of asteroid mining isn’t new; authors imagined it long before 1976:

- 1898 – Garrett P. Serviss, Edison’s Conquest of Mars

- 1952 – Robert A. Heinlein, The Rolling Stones

- 1963 – Poul Anderson, Tales of the Flying Mountains

Sitchin was actually less imaginative than turn-of-the-century pulp writers. Even the fictional Martians in 1898 skipped planet-based slave labor and went straight for the asteroids.

8. Counter-Rebuttals You Might Hear

❓ “Maybe the Anunnaki needed Earth’s specific isotopic mix of gold.”

• Isotopes of gold are created in supernovae and neutron-star mergers; the mix is uniform across the solar system. An asteroid and Earth gold are chemically identical.

❓ “Couldn’t gravity assist from Earth make shipping easier?”

• Gravity assists don’t change the fact that launching from Earth costs huge fuel. From an asteroid you can hoist the cargo and glide it inward using solar sails.

❓ “Slaves are cheap energy.”

• Not in biology: you must provide food, water, housing, and medical care—or lose productivity. Robots run on sunlight, don’t revolt, and can be shut off at night.

9. Where the Real Evidence Points

- We’ve already retrieved asteroid samples with JAXA’s Hayabusa2 and NASA’s OSIRIS-REx. Both missions confirmed rich inventories of iron, nickel, cobalt, and precious metals.

- In 2022 the U.S. government added asteroid mining to its Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, granting companies legal rights over what they collect. Politicians aren’t prone to passing laws about impossible ideas.

- Global investment firms like Morgan Stanley estimate the space-resource market could hit \$1 trillion annually by 2040. No mention of Anunnaki labor plans in those reports.

10. Big Picture: What Would Aliens Actually Want?

Advanced civilizations likely value data, energy, and survivability far more than physical gold. Precious metals matter for circuitry and catalysts, but those are means to an end: building robust interstellar infrastructure. The fastest route to those metals is—again—low-gravity, high-concentration asteroids.

If ETs ever swing through our neighborhood, they’d probably:

- Scan for suitable rocks using telescopes and spectral analysis.

- Dispatch autonomous harvesters.

- Haul refined ingots home or to an orbital manufacturing hub.

Humans, meanwhile, might not even notice—just as fish in the Pacific rarely notice when a cargo ship passes overhead.

11. Conclusion (TL;DR)

Aliens don’t need human gold miners. The physics is against it, the economics is against it, and the archaeological record is silent on it. In contrast, asteroid mining is easy, efficient, and already on humanity’s near-term roadmap.

So the next time a social-media video pops up claiming we’re the product of an ancient cosmic HR department, remember:

- Zero-gravity rocks beat high-gravity planets.

- Robots beat reluctant bipeds.

- Evidence beats speculation.

And if you still crave a story about aliens digging holes on Earth, pick up a vintage sci-fi paperback—you’ll get better plots and fewer translation errors.

Further Reading

- “Asteroid Mining Gives Companies Hope in the Search for Rare Metals” – Discover Magazine

https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/asteroid-mining-gives-companies-hope-in-the-search-for-rare-metals - NASA’s Psyche Mission Page

https://www.nasa.gov/psyche - “Enough to Make Everyone Rich: This Golden Asteroid Is Valued at \$100,000 Quadrillion” – Business Today

https://www.businesstoday.in/science/story/enough-to-make-everyone-rich-this-golden-asteroid-is-valued-at-100000-quadrillion-448124-2024-09-30

Happy space-prospecting—no pickaxe or alien overlord required.

Science fiction that features asteroid mining before Zechariah Sitchin’s “12th Planet”:

1898: Garrett P. Serviss’s Edison’s Conquest of Mars, which was endorsed by Thomas Edison himself, depicts Martians mining asteroids for gold. This is considered one of the earliest examples of asteroid mining in science fiction.

1932: The pulp era saw the rise of asteroid mining as a popular theme. For instance, Murray Leinster’s short story “Miners in the Sky” appeared in Astounding Stories.

1952: Robert A. Heinlein’s juvenile novel The Rolling Stones (also known as Space Family Stone in 1969) portrays the asteroid belt as a new “Gold Rush” frontier with prospectors seeking radioactive ores.

1953: Isaac Asimov’s Lucky Starr and the Pirates of the Asteroids (written under the pseudonym Paul French) features asteroid mining as a key element of the story.

1963-1965: Poul Anderson’s episodic novel Tales of the Flying Mountains, published in Analog magazine (and later as a fix-up in 1970), traces the development of an asteroid mining culture.