A Semiotic Re-evaluation

Chapter 10 of the Sagan Paradox, “From Sun Gods to StarChips,” presents a fascinating hypothesis. At its core, the text argues for a radical re-interpretation of ancient signs (pyramids, myths). It proposes a new code for their decoding – a code made available to us only through modern technology. We can powerfully illuminate this idea through the lens of Umberto Eco’s semiotic theory (A Theory Of Semiotics).

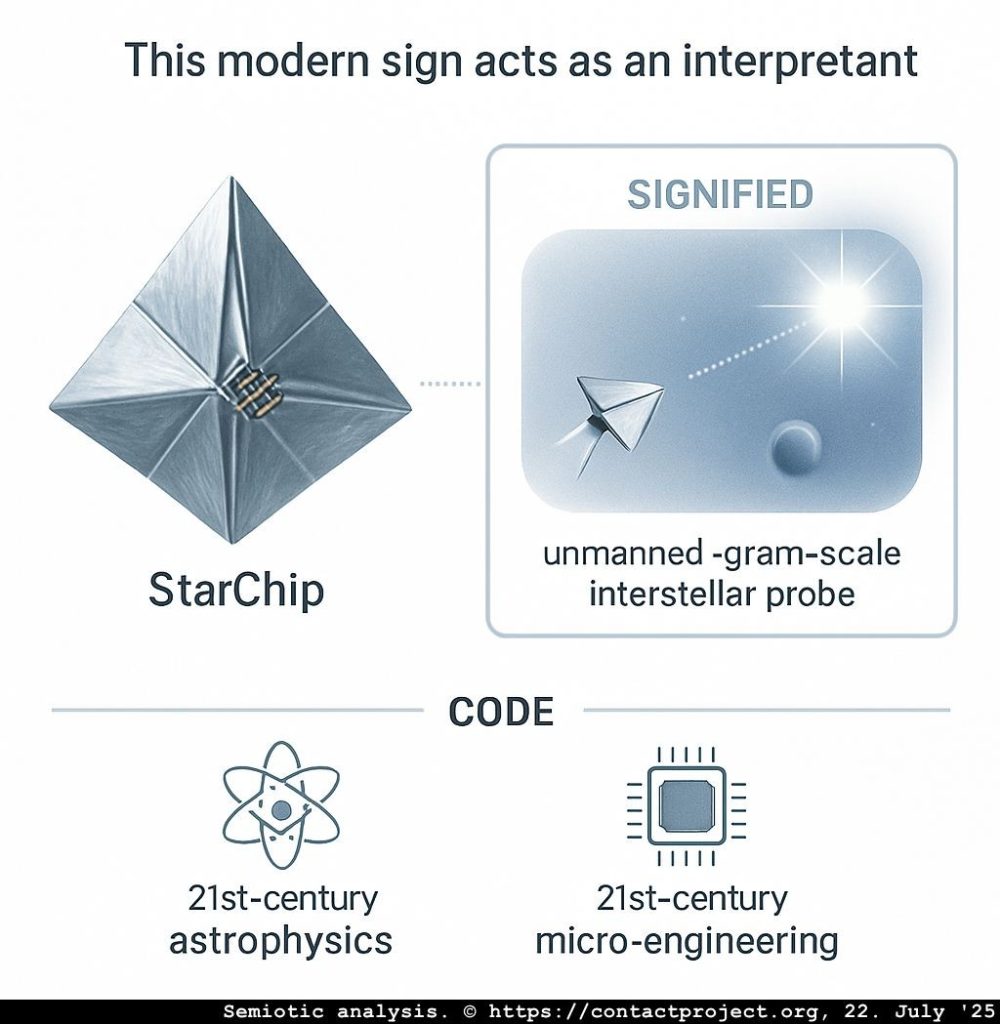

The Sign, the Code, and the Modern Interpretant

Umberto Eco posits that the relationship between a signifier (the physical form, like a word or image) and a signified (the concept it represents) creates meaning. Cultural codes govern this relationship. The text’s argument begins by establishing a new, contemporary code.

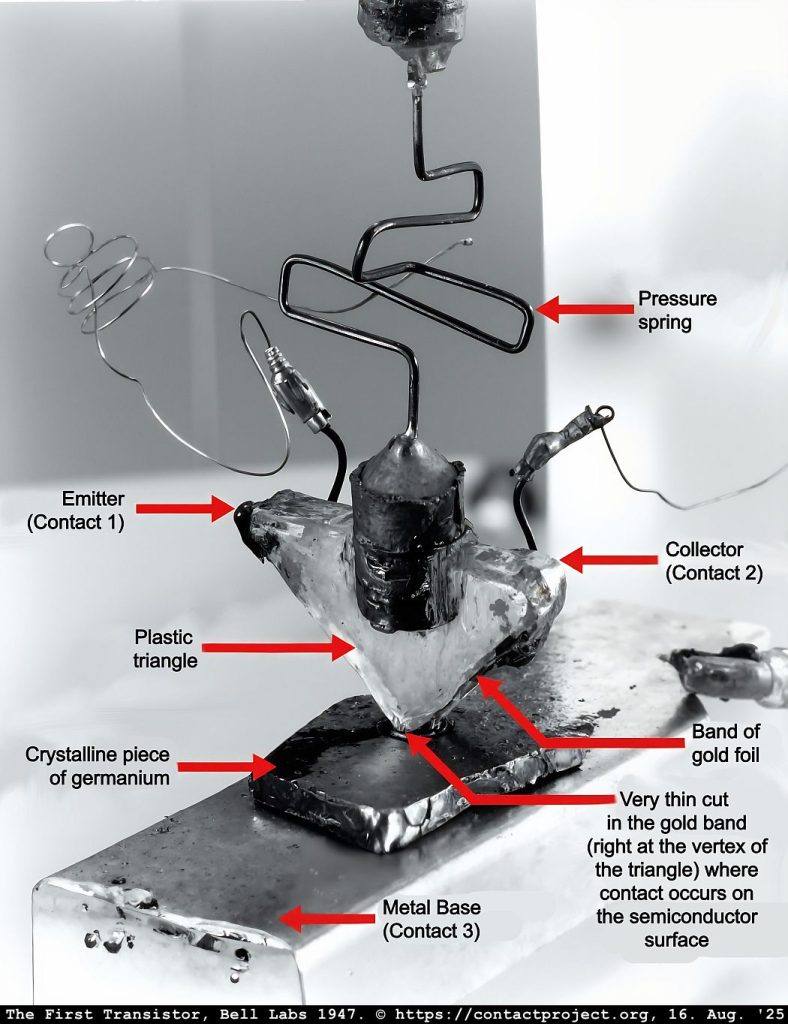

- The Modern Sign: The “Breakthrough Starshot” initiative provides a new, tangible sign.

- Signifier: The “StarChip” probe, a gram-scale, pyramidally-folded solar sail.

- Signified (Denotation): An inexpensive, unmanned interstellar probe capable of reaching nearby stars within decades.

- Code: 21st-century astrophysics and micro-engineering.

This modern sign acts as an interpretant – a new sign in our minds that allows us to re-evaluate older signs. The text successfully resolves “Sagan’s Paradox” not through philosophical argument. Instead, it demonstrates a shift in the technological code. Scientists can now achieve with a few kilograms of material what they once thought required ‘1% of the mass of all stars.’ This establishes the plausibility of the signifier (an interstellar probe) existing.

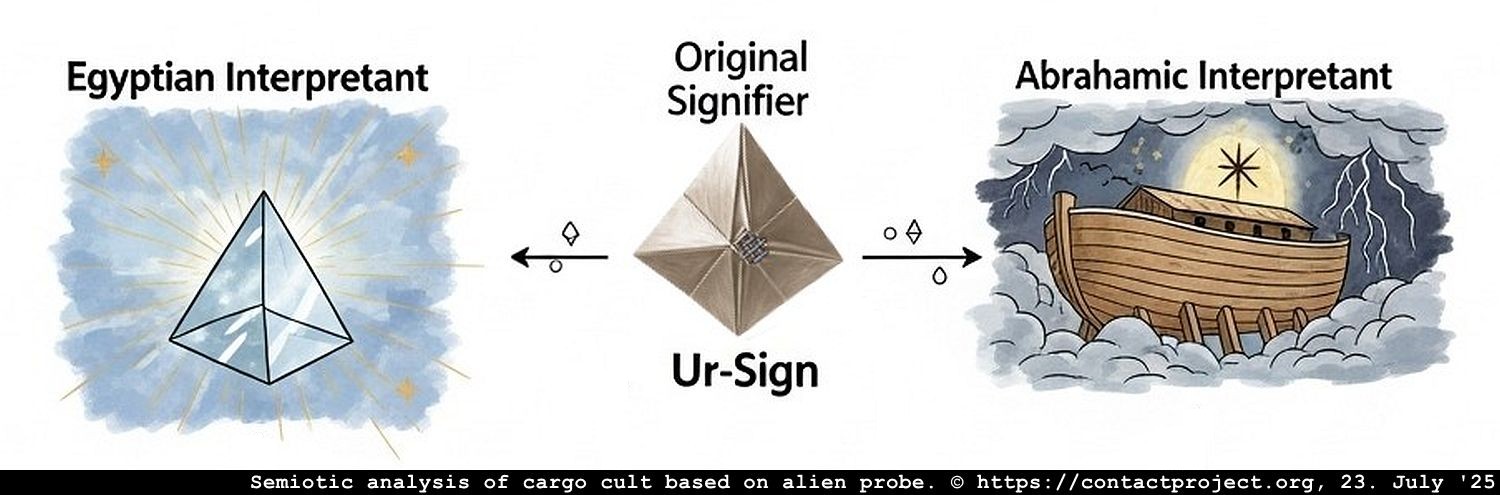

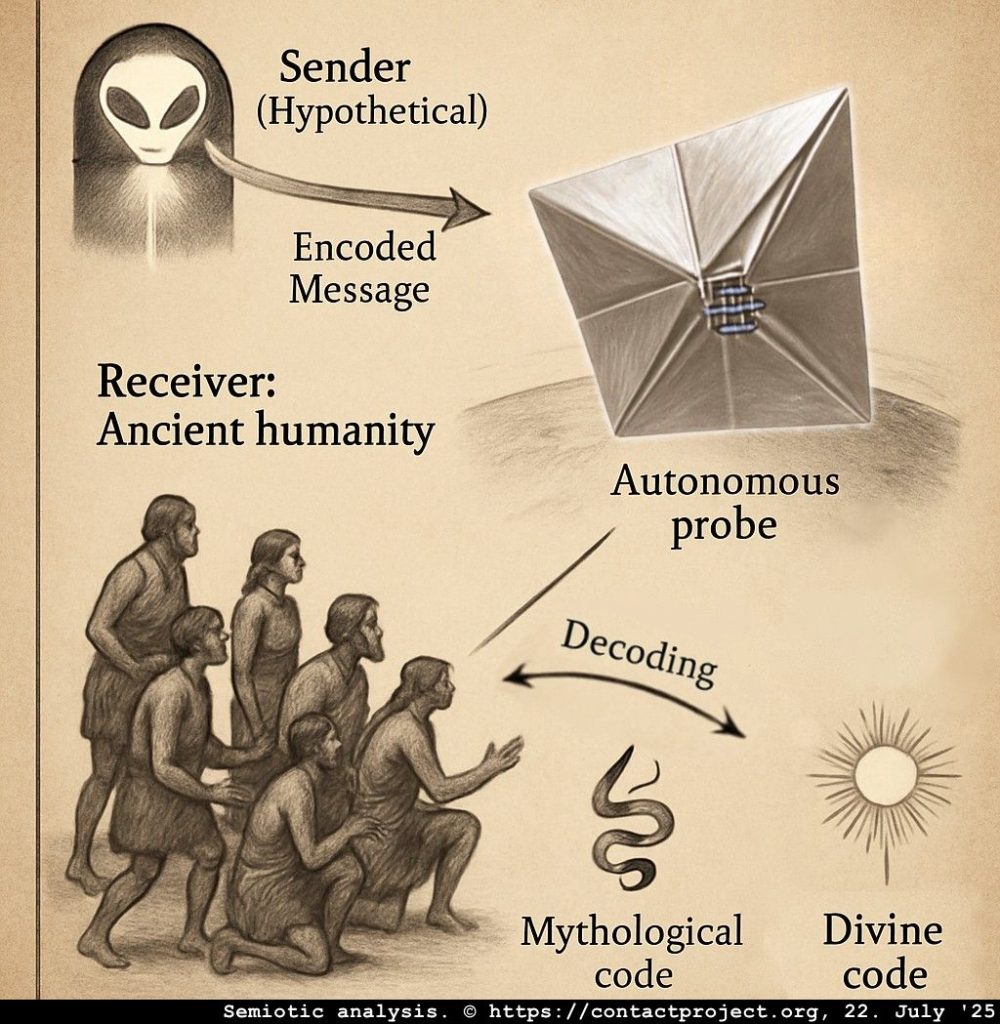

Aberrant Decoding: The “Cargo Cult” Hypothesis

The central thesis of the text is a classic case of what Eco termed aberrant decoding. This happens when someone interprets a message with a different code than the one the sender used. We hypothesize a prehistoric instance of First Contact as the ultimate example of this.

Imagine the following scenario:

- The Sender (Hypothetical): An extraterrestrial intelligence.

- The Message (Encoded): An autonomous probe, possibly resembling a “StarChip,” arrives on Earth. Its “meaning” is purely technological – a device for exploration. The code is one of advanced physics and engineering.

- The Receiver: Ancient humanity.

- The Decoding: Lacking the code of advanced technology, our ancestors could not interpret the object for what it was. They applied the dominant codes available to them: the mythological and the divine.

Thus, a technological artifact (the signifier) was aberrantly decoded. Its signified was not “interstellar probe” but “divine messenger,” “primordial creator,” or “celestial vessel.”

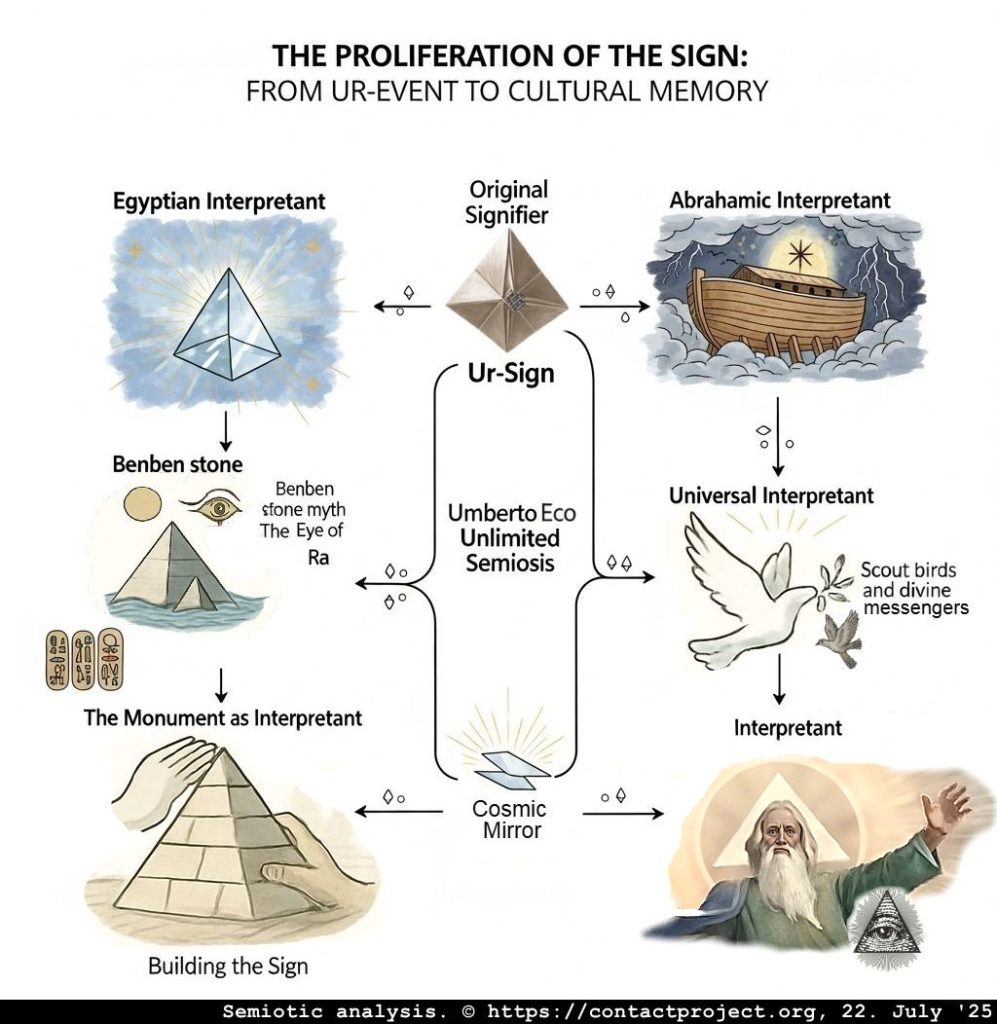

The Proliferation of the Sign: From Ur-Event to Cultural Memory

Eco’s concept of unlimited semiosis explains how a sign can generate an endless chain of subsequent signs (interpretants). The text argues that this single, misunderstood technological event (the “Ur-Sign”) rippled through human culture, creating a web of interconnected myths and symbols.

- The Original Signifier: A pyramidal, reflective object descending from the sky and perhaps associated with a body of water (a common landing necessity).

This signifier generated multiple interpretants across different cultures, all retaining fragments of the original form and context:

- The Egyptian Interpretant: The signifier becomes the Benben stone, the pyramidal mound rising from the primordial waters of Nu, from which the sun god Atum-Ra emerges. The probe’s act of searching becomes the myth of the Eye of Ra. This is a “sentient probe” sent to find his lost children.

- The Abrahamic Interpretant: The signifier’s shape – a stable structure offering salvation from water – is remembered as Noah’s Ark. Recent analysis of the Dead Sea Scrolls suggests a “pyramid-like roof” that powerfully reinforces this connection. It is not that the ark was a pyramid. Instead, they mapped the memory of a pyramidal savior-object onto the story of the ark.

- The Universal Interpretant: The probe’s function as a traveler from an unknown place becomes the recurring motif of scout birds and divine messengers (e.g., the dove in the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Bible). These birds were sent across the water to find a home for humanity.

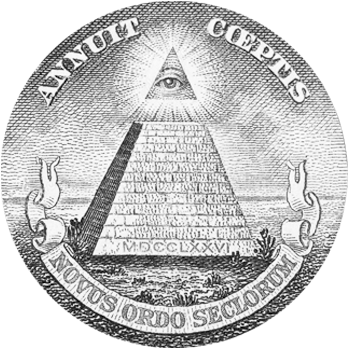

The Monument as Interpretant: Building the Sign

The most profound outcome of this aberrant decoding, according to the text, is not just mythological but architectural. Faced with an awe-inspiring event they interpreted as divine, ancient peoples sought to reconnect with it. They did so by recreating the signifier.

The pyramids, therefore, are not alien artifacts. In semiotic terms, they are a monumental, physical interpretant. They are humanity’s attempt to reproduce the form of the divine visitor. This is a grand act of imitation meant to venerate the original event and perhaps solicit its return. The pyramids are the ultimate expression of a prehistoric “cargo cult” – a monument built not by aliens, but in memory of them.

Conclusion: A New Reading of History

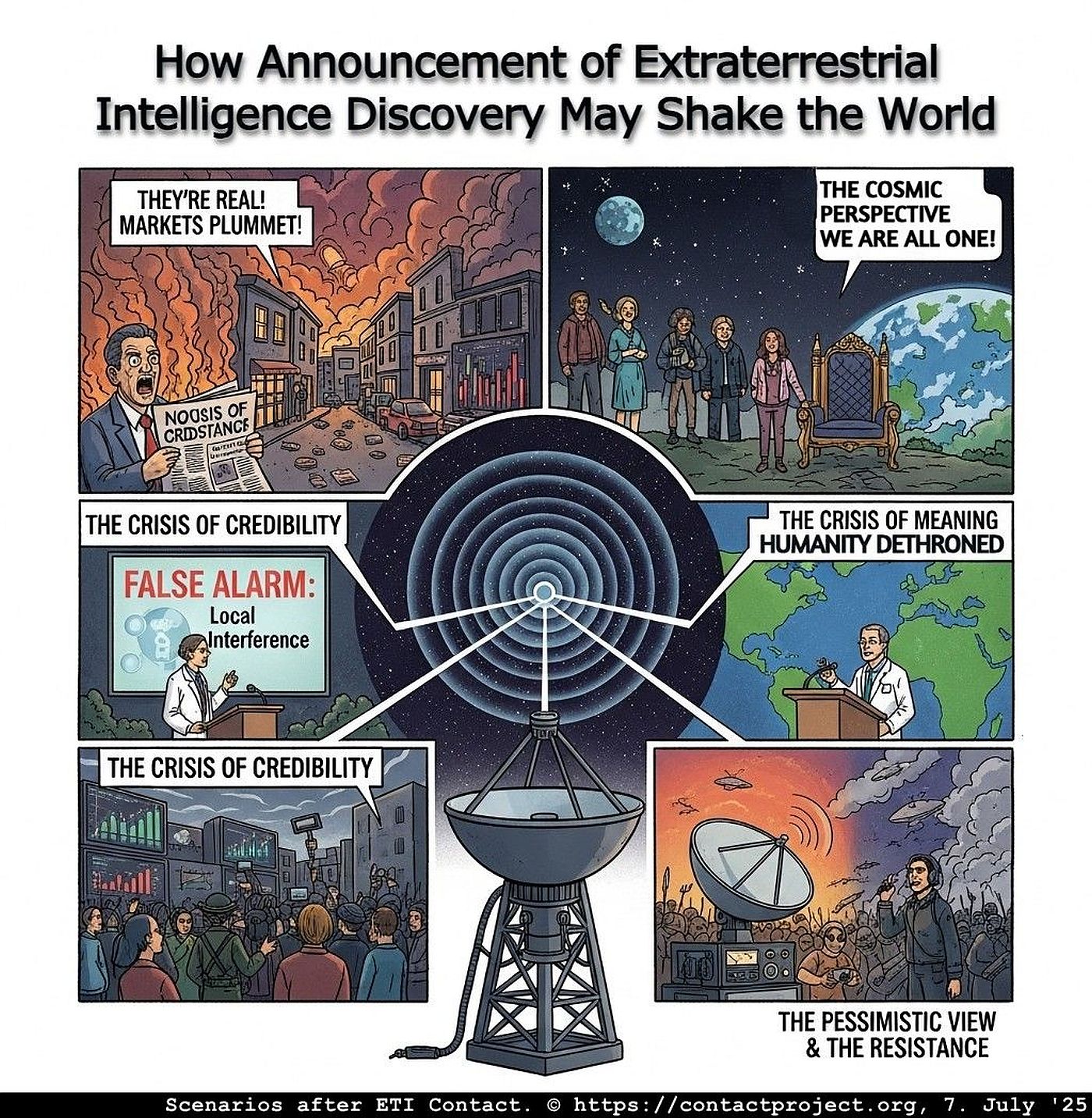

By applying a semiotic framework, we can see that the argument in chapter 10 of the Sagan Paradox is not a simple “ancient astronauts” theory. It is a more nuanced claim about meaning, memory, and interpretation. It suggests that our ancestors witnessed a signifier they could not comprehend. Consequently, they spent millennia processing it through myth, religion, and architecture and signs.

The “Cosmic Mirror” metaphor at the end is apt. The search for extraterrestrial intelligence forces us to re-examine our own signs. The “Breakthrough Starshot” project does not just offer a future of exploration. It also provides a new code, a key that might unlock the meaning behind our most ancient and enigmatic symbols. The pyramids cease to be just tombs or temples. They become signs of a profound encounter, not with alien builders, but with human awe in the face of the unknown.

#SaganParadox #CargoCultTheory #AncientMysteries #Semiotics #PyramidDebate #BreakthroughStarshot #StarChip #UmbertoEco #CosmicMirror #AlienOrigins