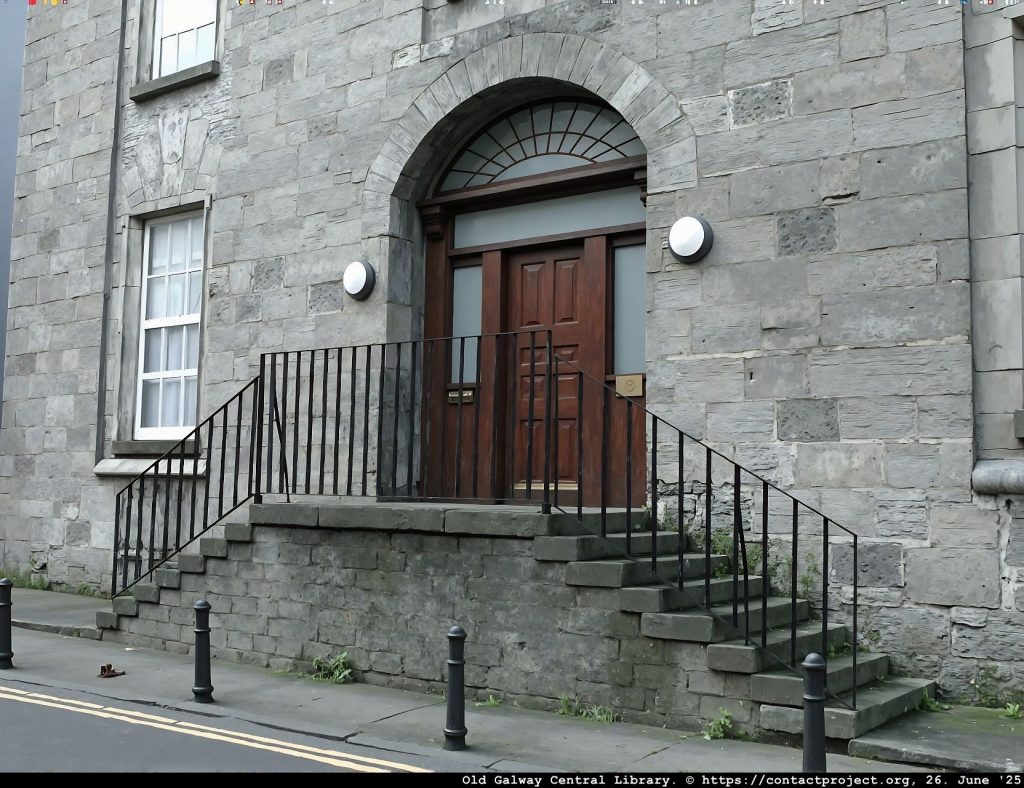

In 1985 I was living in Galway, on the west coast of Ireland. I regularly raided the local library in Augustine Street for reading material. It no longer looks like this, but I remember walking up the stairs on the left:

The Mysteries of Pulsars Capture My Imagination

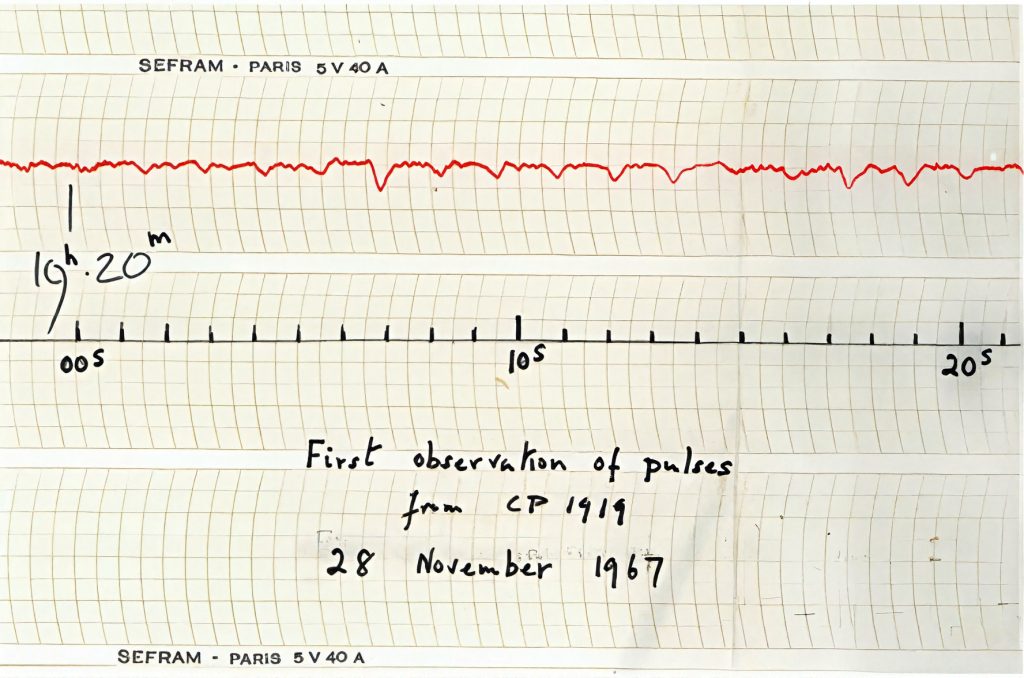

There, I discovered a book about pulsars. As I read, I was struck by the remarkable characteristics of these cosmic phenomena – they emitted incredibly regular radio pulses, seemingly ticking like celestial clocks. Something about their precise periodicity raised a suspicion in my mind: Could these signals be of artificial origin? The idea gnawed at me. It seemed almost too perfect, too synchronized, to be purely natural.

Delays and Doubts: The Scientific Community’s Caution

What puzzled me even more was the fact that the researchers who first detected pulsars waited nearly two years before publishing their findings. When they finally did, they explained the regular radio transmissions as the result of some natural astrophysical process – perhaps rapidly spinning neutron stars or some other exotic object. But I couldn’t shake the feeling that something was being hidden, or at least not fully explored. Why delay the publication? Why rush to explain away the strange signals with a natural cause, when they could just as easily be a message – or evidence – of intelligent life?

A Personal Mission: Reaching Out to a Nobel Laureate

I found myself unable to let go of the thought. I decided I had to try and get some answers directly from someone who knew the science firsthand – Professor Antony Hewish himself, the Nobel laureate who played a key role in the discovery of pulsars.

The walk to the phone booth on Eyre Square was not long – just a few minutes – but to me, it felt like a journey into the unknown. I passed by the familiar sights: the cobblestone streets, the bustling cafés, and the distant clang of the clock tower. The square was busy with people, their conversations and footsteps creating a constant hum. I could feel the cool breeze on my face, carrying the faint smell of brewing coffee from nearby cafés, mingling with the crisp air of a typical Irish day.

Making the Call: Asking the Expert About Artificial Origins

As I approached the square, I paused briefly to steady my breathing. I reached into my pocket, clutching the handful of Irish pound coins I had carefully gathered for this purpose. I looked at the phone booth, a small, glass-panelled box standing at the corner of the square, slightly worn but functional. Its faded paint and the faint smell of old metal reminded me of countless moments of waiting and hope.

I stepped inside, feeling the cool metal of the door handle against my hand. The interior was dimly lit, with the faint glow of the coin slot and dialing pad. I took a moment to collect myself. The hum of the city outside seemed to fade into the background as I lifted the receiver and inserted the coins one by one into the slot, hearing the satisfying clink as they dropped into place.

The phone was a rotary-style model, but it worked, reliable and straightforward. I stared at the dial pad, my fingers trembling slightly as I entered the number for the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge. The line was long-distance, and I had only a limited amount of coins. I whispered a quiet prayer that the call would go through.

The Interview

Finally, I heard the connection click. A calm, measured voice answered.

“Hello?”

“Professor Hewish?” I asked, trying to keep my voice steady.

“Yes, speaking,” came the reply.

I hesitated for a moment, my mind racing with questions. Then I blurted out, “I’m calling to congratulate you on the discovery of pulsars.”

There was a brief pause, and I could almost hear him smiling on the other end of the line.

He thanked me politely, then I took a deep breath and asked, “I find the subject absolutely fascinating, and I was wondering… are you absolutely certain that pulsars are not of artificial origin?”

He responded with quiet confidence, “Yes, I am certain.”

And then he proceeded to explain, his voice steady and reassuring:

“Pulsars are fascinating objects. They are highly magnetized, rapidly spinning neutron stars, remnants of massive stars that have gone supernova. As they rotate, their intense magnetic fields funnel particles toward their magnetic poles, which act like cosmic lighthouse beams. When these beams sweep past Earth, we detect them as highly regular radio pulses.”

Reflections Under the Galway Sky

I listened intently, my mind swirling with his explanations, ones I’d heard before, yet they only deepened my curiosity. I asked again, perhaps more insistently:

“And you are 100% sure that pulsars are not of artificial origin?”

Hewish chuckled softly on the line, “Yes, absolutely certain.”

I thanked him for his time, and before used up all my coins, I ended the call. Stepping back onto the street, I looked up at the grey, cloudy sky, pondering the vastness of space and the mysteries it still held. The conversation left me with a lingering question: could we someday truly find signs of intelligent life out there?

One Second of Error in 30 Million Years

The universe’s most precise timekeepers, the most stable pulsars, are so remarkably accurate that they would drift by only a single second over tens of millions of years. Their stability rivals – and in some respects even surpasses – that of our most advanced atomic clocks.

The most stable known millisecond pulsar, designated PSR J1713+0747, exemplifies this extraordinary precision. Its rotational period is so consistent that it would accumulate an error of just one second after approximately 30 million years.

When we talk about the superiority of pulsars as cosmic clocks, we’re referring to their ability to keep perfect time over millennia, far beyond the reach of any human-made clock. Engineers can build clocks that lose only one second in 300 billion years, but such devices are fragile, often breaking down within a few decades. Pulsars, on the other hand, can continue their steady ticking for billions of years, offering an unmatched cosmic standard of time.