Estimated reading time: 15 minutes

In memory of the crew of NASA Mission STS-51-L, January 28, 1986.

Back (L-R): Ellison Onizuka, Christa McAuliffe, Gregory Jarvis, Judith Resnik.

Front (L-R): Michael J. Smith, Francis “Dick” Scobee, Ronald McNair.

Author’s Note

In early January 1986, two weeks before the Challenger disaster, I experienced a lucid dream that, in retrospect, mirrored the interior perspective and emotional atmosphere of the shuttle’s middeck during the crew’s final minutes. At the time, I had no knowledge of the middeck layout, the seating arrangement, the behavior of the hatch, or Ronald McNair’s training in the Personal Rescue Enclosure – yet the dream contained elements consistent with all of these.

To me, this was not coincidence.

It was a form of precognition.

I do not ask readers to accept this interpretation, only to understand that the dream preceded the event, returned with force when the tragedy unfolded, and remained vivid across the decades. It is the reason I wrote this account at all – because what happened in that dream has never left me, and its alignment with later-known facts continues to defy simple explanation.

– Erich Habich-Traut

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The January 1986 Dream

- 3. FACT CHECK: Crew Configuration

- 4. The Middeck Environment

- 5. Liftoff

- 6. FACT CHECK: The Challenger Accident Findings

- Reconstructed Flight Path

- 7. Survivability Analysis

- 8. FACT CHECK: The Hatch Could Not Be Opened

- 9. FACT CHECK — The Rescue Ball (PRE)

- 10. Reflection

- 11. Eyewitness Accounts from Investigators

- 12. Conclusion

1. Introduction

In January 1986, I was living in Galway, on Ireland’s Atlantic coast, in a quiet rented house shared by three very different lives: Ida, a retired schoolteacher and our landlady, who had spent most of her working life in London; Sheila, a young student from University College Galway, earnest and full of plans; and myself, 22 years old at the time.

Each evening we would gather in the sitting room around the television – mugs of tea in hand, the gas fire hissing softly – to catch the days news from the world beyond the bay. It was there, together, that we watched the launch of Challenger.

At first, everything seemed routine: the countdown, the billow of steam, the slow, majestic rise of the Shuttle through the pale Florida sky. The commentators were calm, practiced. We watched the white exhaust trail twist upward, a small miracle made ordinary through familiarity.

Ida, who had spent a lifetime with children, seemed especially shaken. “All those schoolkids watching,” she murmured. She was thinking, I knew, of the Teacher-in-Space, Christa McAuliffe – the symbol of a hopeful new era in public engagement with spaceflight.

Christa McAuliffe also had Irish roots, not too far from Galway. Genealogical research indicates that her great-grandmother Mary was from Athlone. Clicking her portrait will open the PDF: A Heritage Defined: The Irish Roots of Christa McAuliffe in County Westmeath.

That night, long after the television went dark and the last reports faded into static, I sat by the window, watching the streetlights gleam on the wet pavement. The explosion replayed endlessly behind my eyes – white bloom, branching smoke, sudden emptiness. As I stared into the dark, another memory rose to the surface: a dream I had had earlier that month, nearly forgotten until that moment.

2. The January 1986 Dream

One night in the first half of January 1986, I had dreamt of being in a bright, enclosed space. I didn’t recognize the place – the clean, almost metallic light illuminated the smooth walls curving around me.

Now, in the wake of what had happened, that dream returned with an unsettling clarity. I couldn’t shake the sense that it had somehow brushed against the same moment.

DREAMSCAPE

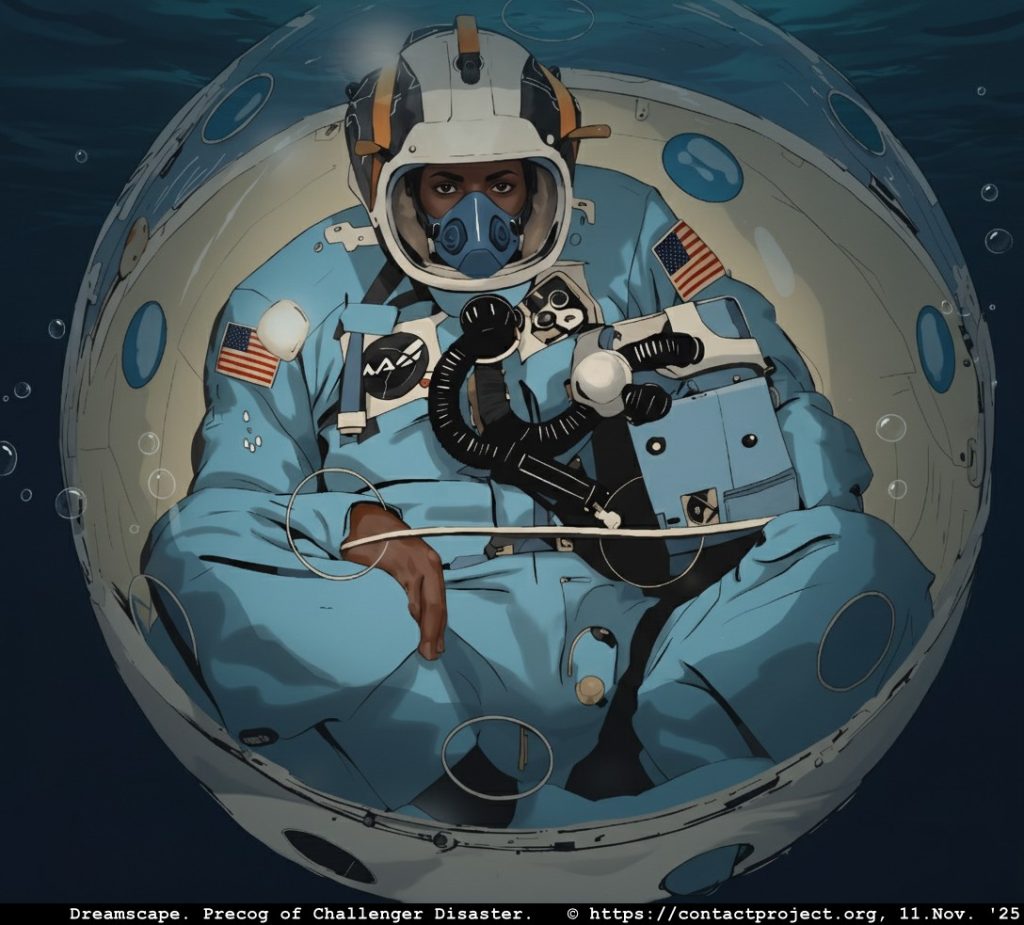

In the dream I was somebody – and that somebody, judging by the perspective and position, was almost certainly astronaut Ronald McNair, seated in position S5 on the middeck.

From that vantage point I looked toward the back of a woman seated ahead of me. Her long hair floated gently inside her helmet. The cabin was dim but alive with the hum of systems and the quiet concentration of the crew.

3. FACT CHECK: Crew Configuration

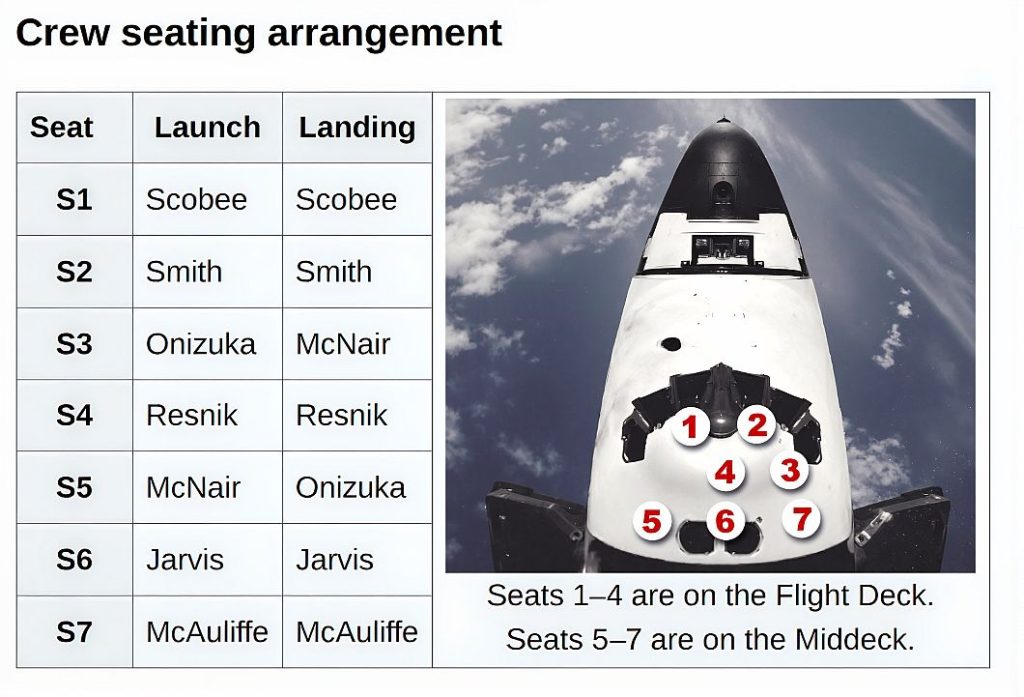

The following image, based on an actual STS-51-L training photograph, reflects the layout. Gregory Jarvis is in the center, Christa McAuliffe to the left, and Ronald McNair near the crew hatch in the back to the right.

This configuration matches the dream’s spatial viewpoint of Ronald McNair.

DREAMSCAPE — Anticipation Before Launch

I remember a feeling of anticipation – we were finally going somewhere, after all the long preparations.

4. The Middeck Environment

The mid deck of the Space Shuttle was a slightly claustrophobic environment. Astronauts often described it as enclosed and functional, lit mainly by cabin lights and reflections from above. It had no open windows during missions.

In the final seconds before liftoff, technicians sealed the hatch, locking the crew inside their small world of air and anticipation. The cabin filled with the soft hiss of circulation and the steady, rhythmic voices of the flight deck counting down. Helmets gleamed under the instrument lights, visors still raised – a last breath shared among crewmates.

The illustration above was inspired by a photo of a training session. It shows a likeness of Ronald McNair sitting next to the side hatch. A ladder behind him connects the middeck to the flight deck above. His crewmates, Jarvis and McAuliffe, are seated in front of him to the left (his right).

The shuttle crew was strapped into their seats before liftoff by the “closeout crew”. The seats in the liftoff position were not vertical but horizontal. In other words, the crew was lying in the seats on their backs.

The view the middeck crew “enjoyed” was minimal:

The walls made you feel like you were sitting inside a filing cabinet. Locker doors ran from floor to ceiling, each one the size of a briefcase lid.

5. Liftoff

At the call to secure, visors snapped shut – one after another, sealing each astronaut into the sound of their own breathing.

The rising rumble built into a physical roar. The structure flexed; straps tightened; acceleration pressed everyone deeper into their seats.

Then something unexpected:

The pilot’s voice: “Uh… oh.” (This exclamation is documented in the recovered cockpit recorder.)

At T+73 seconds, the Space Shuttle Challenger disintegrated after catastrophic booster O-ring failure.

And then – silence?

DREAMSCAPE – Panic and Training

We’re inside the body of Ronald McNair.

“One of the persons in my field of view was a woman.

Suddenly something unexpected happened. There was panic and shouting.

I felt preternaturally calm. The astronaut training kicked in.

I feared to loose air and therefore tried to activate the emergency air supply.”

6. FACT CHECK: The Challenger Accident Findings

1. INVESTIGATION OF THE CHALLENGER ACCIDENT

2. Report to the President

- The crew cabin remained largely intact during breakup.

- It ascended before beginning a free-fall.

- The crew module lost all power and communications. The crew tried to restore power.

- During the descent, astronauts Smith (S2), Onizuka (S4), and Resnik (S3) activated their Personal Egress Air Packs (PEAPs), Commander Scobee (S1) did not. The remaining packs were not found, so we don’t know if they were activated.

Even if the cabin gradually lost pressure, investigators concluded that the crew would have stayed conscious long enough to glimpse the ocean surface rising toward them.

No evidence was found for a sudden, catastrophic depressurization. (A sudden depressurization would have led to blackout, irrespective of PEAP air supply or not.)

Reconstructed Flight Path

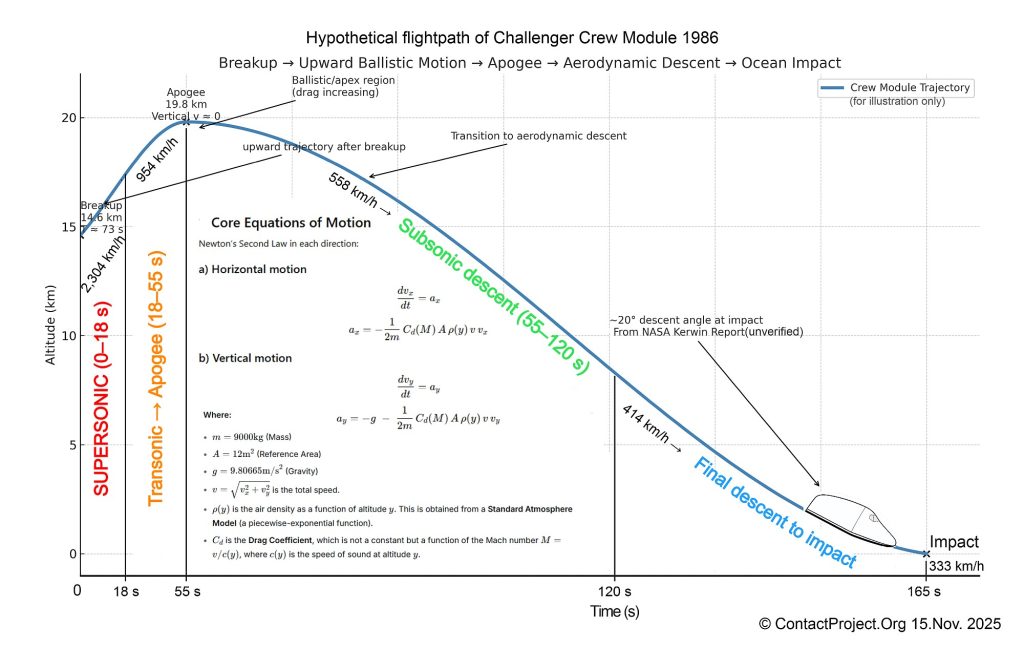

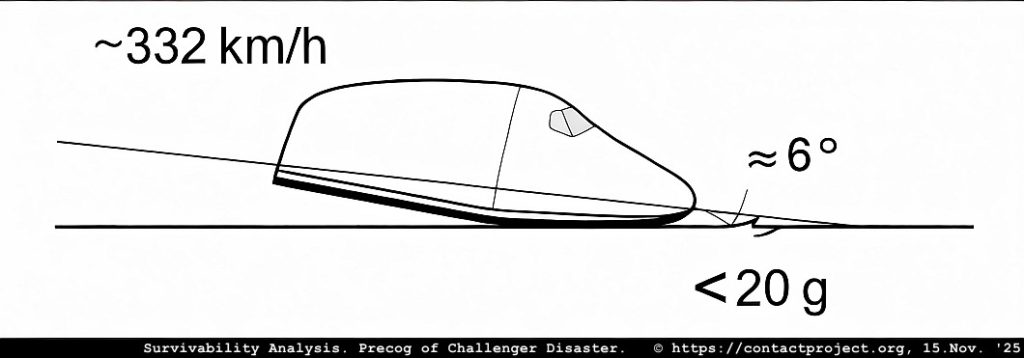

This is the reconstructed flight path of the Challenger crew module – from breakup to ocean impact, just 167 seconds later:

The graphic shows how the cabin continued rising for nearly a minute before beginning its final descent, passing through supersonic, transonic, and subsonic phases. I’ve added the real physics equations and timing so the entire sequence can be understood clearly.

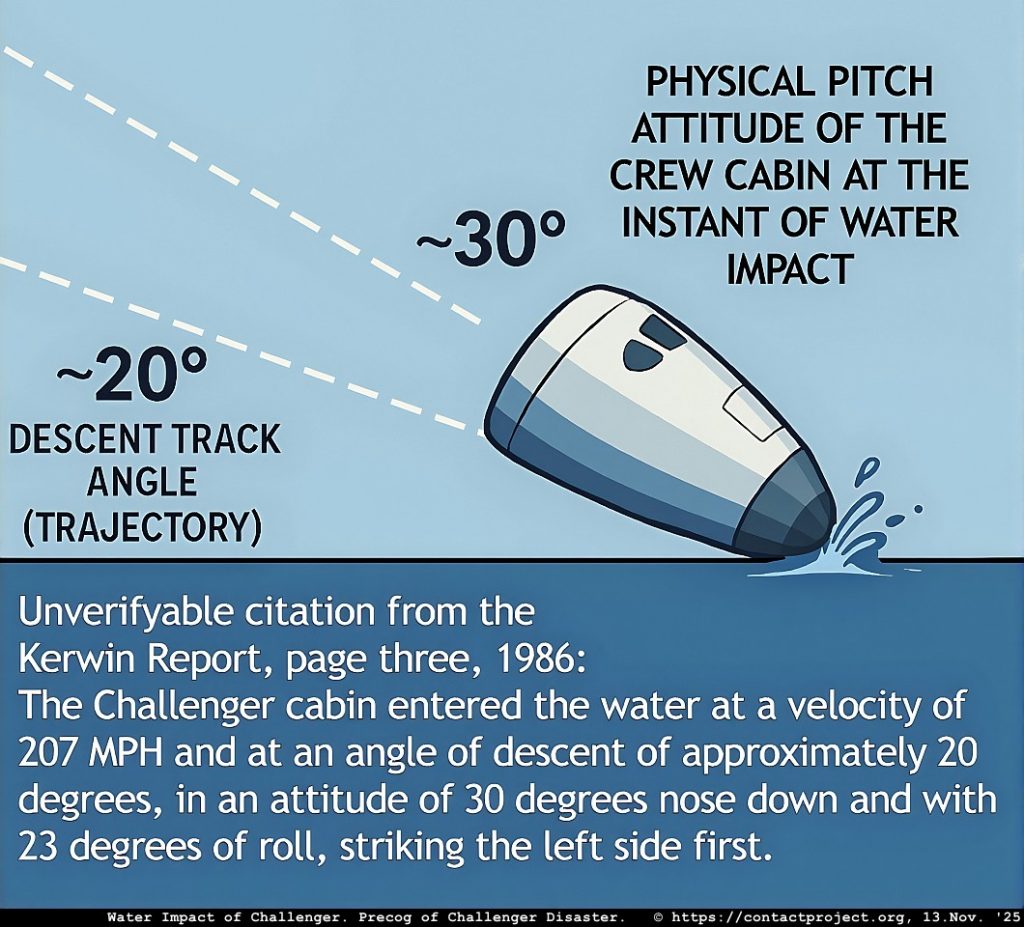

Then, the shuttle crew compartment hit the water with a speed of approximately 207 mph (≈ 333 km/h):

- 20° degrees below horizontal (a shallow glide)

- 30° degrees nose-down

- about 12° degrees roll

The finding of a “30° nose-down” attitude (and an associated roll) was not the attitude at the moment of breakup. Instead, it was the reconstructed attitude of the crew compartment at the moment it hit the water.

The analysis of the physical, “forensic” damage to the recovered cabin is how they determined its orientation at impact. The 20° trajectory, by contrast, was calculated from radar data tracking the cabin’s ballistic arc before impact.

My physics simulations show that G-force estimates range from 60 g to 386 g. This wide range shows that the final G-force is almost entirely dependent on one unknown factor: how much of the cabin’s surface area hit the water in the first milliseconds of the glancing impact.

7. Survivability Analysis

Due to the nature of my lucid dream, a large part of my deliberations focused on the possible crew survival. For a slim-chance survival (≤20 g for ~100 ms) at ~92.5 m/s, the crew module would have needed not a plunge, not a dive, but a glide into the water at a very small angle (a few degrees). Using a stopping depth (distance) of 0.2–0.3 m in water, the vertical-speed limit is set by:$$ a \approx \frac{(v \sin\theta)^2}{2s} \le 20g $$ which implies: $$ \theta \lesssim 5.5^\circ\text{–}6.7^\circ $$

Even with a very generous stopping distance of 1 m, the angle would have to have been: $$ \theta \approx 12^\circ $$

Thus the necessary water-entry angle for any survivability would have been single-digits (≈5.5° – 6.7°), flatter than what airliners can achieve during a controlled water landing. This scenario was physically impossible.

The following recapitulation of the event is from Ronald McNair’s perspective. Perhaps this January 1986 dream was NOT a dream, it was a hope.

DREAMSCAPE – Attempting Escape

At (water) impact I briefly lost consciousness. When I came to, I tried in a daze to move toward the airlock – perhaps the mid-deck airlock (it was actually the crew ingress/egress hatch, I sat right next to it) -to get out, but it was stuck.

I thought it did not open because of pressure from the outside.

The airlock had been designed to open to the vacuum of space, or to neutral atmospheric pressure, but not against hydrostatic pressure from water.

8. FACT CHECK: The Hatch Could Not Be Opened

This is correct. The hatch opened to the outside. Water pushing from the outside would have prevented its opening. After the Challenger accident, NASA added explosive bolts to this hatch to allow emergency jettison – but even that system was not intended for underwater use.

DREAMSCAPE – The “Air Bubble”

“I’m sinking into darkness as water engulfs me, frantically pawing at the sealed airlock that refuses to open.

I try again to activate the emergency air supply.

I hope the emergency air pack might somehow keep me – and the woman beside me – from drowning. The situation is similar to one we once trained for – a hull breach caused by a micrometeorite impact – where the pack might sustain us. I hope it will keep us from drowning.

Then the moment turns surreal.

I’m frantically trying to crawl into something like a balloon and inflate it with air; if I can get inside, I might be able to breathe and survive. But I’m struggling and can’t get inside.

Regret sears through me that I never got the airlock open before loosing consciousness.”

End of dream, 14. January 1986.

9. FACT CHECK — The Rescue Ball (PRE)

NASA’s first six female astronaut candidates (1978) pose with a prototype Personal Rescue Enclosure (the white “rescue ball”) at Johnson Space Center. The 36‑inch sphere was barely large enough for a person to curl up inside with an hour’s supply of air, and it was used to test astronaut candidates for claustrophobia during training.

In reality, Ronald McNair’s Personal Rescue Enclosure (PRE) training experience is the real-life source of the dream’s “air bubble” imagery. McNair was selected in 1978 as part of Astronaut Group 8, having to prove he could handle extreme confinement by climbing inside the PRE during training.

The PRE itself never progressed beyond the testing stage and was never used on actual Shuttle missions.

The memory of being sealed in that tiny enclosure left a deep imprint. The dream’s scene of curling inward for survival – huddling in a small bubble of air – echoes McNair’s real-life ordeal of contorting himself inside the PRE, seeking comfort in a pocket of air and trusting that that little bubble of oxygen could keep him alive. Alas, it was just a dream; because no such rescue ball was on the shuttle.

10. Reflection

I rarely remember dreams, and few have ever been remarkable.

This one was.

It was also a lucid dream: I attempted to influence its outcome, but could not.

11. Eyewitness Accounts from Investigators

Journalist Denis E. Powell of The Miami Herald (1988) summarized the post-recovery findings:

“When the shuttle broke apart, the crew compartment did not lose pressure, at least not at once.

There was an uncomfortable jolt—‘a pretty good kick in the pants,’ as one investigator described it—but it was not severe enough to cause injury.

This probably accounted for the ‘uh-oh’ that was the last word heard on the flight deck tape recovered from the ocean floor two months later…”

12. Conclusion

Three decades have passed since that terrible morning, and only now have I found the courage to put this experience into words and share it openly.

I know that revisiting this tragedy may seem unnecessary or even painful.

Some may wonder why anyone would return to a moment that brought such profound grief – especially when what I describe touches on the final minutes of people who were loved, cherished, and irreplaceable.

The only answer I can give is this:

I remember it.

It lived inside me – two weeks before the world witnessed it.

And carrying it alone for so long no longer felt right.

To the families, I offer my deepest and most sincere apology if these reflections reopen old wounds.

It is not my intention to add to your sorrow.

I can only share what stayed with me, exactly as I experienced it.

The crew of the Space Shuttle Challenger were, and forever will be, heroes –

in their work, in their courage, and in every life they touched.

This is written in memory of all who could not be saved –

whether in waking life, or in dream.

Can we change the past?

I do not know.

But we can honor it.

And this memory is now part of that past.

References

- NASA History Office: Kerwin Report (1986) – “The cause of death of the Challenger astronauts cannot be positively determined.”

- Wikipedia: STS-51-L

- Powell, D.E. (1988). “The Fate of Challenger’s Crew,” Miami Herald Tropic magazine.

- Thirty Years Ago, the Challenger Crew Plunged Alive and Aware to Their Deaths, Gawker (2016).

- Evidence Hints That Astronauts Were Alive During Fall, NBC News (2003).

- NASA / Rogers Commission, Report of the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident (1986).

✅ Fact-Check Summary

| Claim | Status | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Crew cabin survived breakup | ✔ True | Confirmed by NASA & Rogers Commission |

| Descent lasted ~2 min 45 s | ✔ True | NASA radar tracking data |

| Impact speed ≈ 200 mph | ✔ True | NASA estimate, Kerwin Report |

| 3 PEAPs activated | ✔ True | NASA recovery data |

| Cause of accident: SRB O-ring | ✔ True | Rogers Commission |

| Possible crew consciousness until impact | ⚠ Probable | No proof of duration; consistent with NASA findings |

| “At least one survived impact” | ✖ Unsupported | Impact forces (> 200 g) were non-survivable |

| Cabin entered ocean nose-down | ✔ Supported | NASA hydrodynamic analysis (≈ 10–20°) |